THIS DESERT LIFE

GANSU province in the far west of China is an endless sea of windswept PLATEAUS, remote farms, and DESERTED landscapes. It’s also home to some of the most spectacular CYCLING in the world

China probably isn’t the first country you think of when making a bucket list of cycling destinations. It probably isn’t even on most people’s lists of holiday destinations. If it is, most will go to the sprawling metropolis of Shanghai, or the reconstructed Great Wall not far from Beijing.

To someone like me, however, who has lived here for several years and harbours a nagging dislike of the road well-travelled, these itineraries single-handedly miss out on the real beauty of this country. For me, the best of China lies far away from bland, crowded cities and clichéd tourism hotspots, in places less clogged with people and less buffeted by the winds of change — and best viewed from the saddle of a bike.

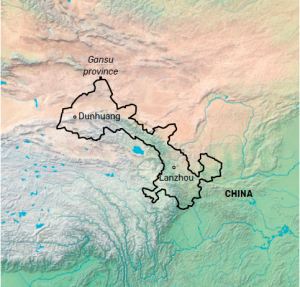

Gansu province in the far west of China is one such place. A 600-mile-long corridor that traces the Chinese side of the ancient Silk Road, Gansu is a flat and fertile strip of land sandwiched between two unforgiving giants of global geography: the Gobi desert to the north and the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau to the south. With a population density of just 140 people per square mile (compared to more than 5,000 per square mile in Shanghai), it’s also extremely quiet.

Three years previously, while studying abroad for my Mandarin degree, I had come to Gansu on a whim with a university classmate, to do a few days’ cycling and see ancient Buddhist cave artwork in the historic town of Dunhuang. The caves were impressive, but what stuck with me more was the world we saw from two wheels. We rode through tiny villages and unspoiled mountains and gorges, enjoying perfect weather, cheap food, and beautiful roads. The utter freedom and simple happiness I felt was unlike anything I’d experienced before; I remember thinking, ‘this is a feeling worth chasing’.

That holiday, we covered 60 miles or so over a gentle few days. Now, with several cycling expeditions under my belt and armed with my own bike, tent, and camera, I was returning to cover the whole 680 miles of the province.

THE TRAIN TO DUNHUANG

Dunhuang is about as far west as you can go in Gansu, and it felt fitting to start my journey in the town which had given rise to the idea of it.

Not wanting to leave my beloved bike at the mercy of airport baggage handlers, I packed her into a soft case and rode the train for more than 20 hours, watching transfixed as the apartment blocks outside the window melted into low rise buildings, then fields, then mountains, and eventually barren, endless desert.

At points, towering white wind turbines would dominate the landscape for miles on end. They were awesome and surreal in their sheer number, spreading across my entire field of vision like a mirage. I was spellbound. Something about the complete emptiness of the desert takes my breath away, and these white giants seemed a testament to that emptiness. It didn’t matter if you put thousands of them here; nobody was around to care. I couldn’t wait until I’d be sleeping alone among them. When we finally arrived at Dunhuang, it was a relief to be enveloped by the cool desert air, and I stared up at the sky, drinking in the stars, which never broke through in the city.

The next morning, I was finally off. To my delight, the roads were much as I remembered them: a mixture of picturesque countryside dirt tracks and smooth tarmac, winding endlessly through stretches of barren sand and seemingly impossible desert farmland.

Rainfall in Gansu is almost non-existent. Dunhuang sees an average of just 5cm a year. The surprising abundance of grazing land, melon fields, fruit orchards and vineyards have been historically supported by groundwater, and more recently by extensive irrigation schemes. Riding through village after village in the baking sun, flanked by shimmering green trees and rows of grapevines, I could have been in southern Italy, aside from the Chinese characters on the road signs and astonished stares I got from any local who happened to pass by. Foreigners on bikes were evidently uncommon in this part of China.

As I was looking for a discreet place to pitch my tent that first night, I heard somebody shout. “Hey! Wait!” Hoping I wasn’t in trouble, I turned around just in time to receive the melon that was being thrust towards me, by a girl who had passed by on an electric truck moments earlier. I guessed she was about 14.

“This is a melon from our farm. Welcome to China!” She rushed over her words, grinning. I looked down at it, surprised, and started to thank her, but I was talking to her back— she was already running towards her truck. That evening, I sat on a rock and ate my melon, revelling in the simple pleasures of the perfect temperature of the breeze, and pink sunset that lit up the sky.

The very next day brought me face to face with the wind turbines I had been so excited to see. Before I left, a friend had asked me what the hardest part of my trip was going to be, and I had answered honestly: these first few days. Heading east from Dunhuang, avoiding highways, my map showed me I would face a stretch of featureless desert with a single road running through it, unbroken for almost 60 miles. I found the idea thrilling. Just me and my bike, trekking from one side of nothing to the other.

Distance and desolation, I was prepared for. What I hadn’t expected was worsening road quality and vicious winds. Around 6 miles into the 53-mile road, things started to worsen; at 20 miles in, thick sand made the going impossible, and I had to start walking. Leaning into the gusts, I sighed at my own stupidity: it shouldn’t have taken a genius to connect the presence of so many wind turbines with a lot of wind.

I tramped on at a snail’s pace for hours, setting my will against the elements, which seemed determined to turn me back. I got back on the bike for short stretches when I could, and put in my headphones to drown out the howling wind and distract me from worrying about my dwindling water reserves. Finally, 8 hours into the day’s ride, the road quality improved enough to ride smoothly once more. I felt as though I could cry as I hopped back into the saddle, buckling with gratitude for the instant tripling of my speed that meant I wouldn’t have to walk through the night with no water.

Around this time, a large, square rock loomed in the road ahead, surrounded by a low fence. A sign informed me that it was a ruin of the Great Wall, almost a thousand years old. I hugged myself, feeling proud that my desert trek had rewarded me with something few others would ever see.

As I continued eastwards, the landscape filled up with villages and towns. It was the middle of harvest season for sunflowers and maize, meaning that the streets of many villages were heaped with drying heads of corn and sunflower husks which filled the air with their thick, sweet fragrance. On several occasions, I stopped to ask if I could take photographs of farmers, one of whom introduced himself as Long Tu. He chattered enthusiastically as he raked out a mountain of sunflower seeds.

“I don’t actually know what they sell for,” he said. “This is my brother’s farm. I’m just here to help. You hungry? Do you want one of our melons?” He led me to their nearby melon field, choosing one for us to share and one for me to put in my bag before promptly inviting me into his friend’s home for lunch. I accepted, feeling privileged to be invited into one of the high-walled houses that I had seen in every village, but never stepped inside.

The owner of this particular house, Cang Ge, was a gruff but friendly man with a deeply lined and tanned face, who set low stools out for us around a foot-high table in his courtyard while his wife prepared noodles and a spicy tomato sauce in the kitchen. “These thick noodles are our traditional food. Everyone makes them fresh at home.

Even I know how to make noodles,” Long Tu told me. “Here, take a bite of this.” He held out a chilli he had picked from the garden, suppressing a smirk. “Only if you try it first,” I said warily. We took a bite at the same time. After a few seconds, it hit me, and I coughed, eyes watering, much to the amusement of everyone present. It’s a source of national pride that foreigners can’t handle Chinese spice.

I ate until I could hardly move, listening to Long Tu and Cang Ge discuss crop prices, amazed by, and grateful for, their unquestioning hospitality.

A DIFFERENT CHINA

I cycled between 18 and 80 miles a day, depending on terrain and how tired I was. When I got to a town, I would take a rest day, washing my clothes in the bathroom sink of my hotel room and enjoy the luxury of hot running water.

In Zhangye, a city about halfway down the Gansu corridor, I paid for a ticket to see the famous Daxiagu rock formations at the insistence of a Chinese friend. The deep red colouring and vast size of the rocky valleys were admittedly awe-inspiring, but I couldn’t muster the same enthusiasm for them as I had for my own discoveries on the road.

Between towns, I would pitch my tent on the grassy banks of rivers I found on Google Maps, behind desert rocks, or in hidden corners of fields, sleeping deeply from sunset to sunrise. Aside from the occasional swarm of mosquitos, the season was perfect for it; in four weeks, I only had one night of light drizzle, and most of my evenings were spent admiring the sunset outside my tent and feeling lucky to bear witness to this wilder side of China so few people seem to know about.

I gravitated toward reservoirs. Camping by them gave rise to some of my most memorable evenings, often in the company of animals that were as drawn to the water as I was: flocks of birds, roaming donkeys or herds of sheep and their lone shepherds.

One of the most extraordinary scenes I came across was a completely abandoned salt village. The rapid economic development of the last 30 years in China has not been spread equally, and it’s not uncommon for entire towns or counties to be drained of their youth, who migrate to big cities in search of higher wages, leaving the elderly and young children behind. This village had nobody left in it at all. It was dominated by a hollowed-out factory; empty houses with smashed windows surrounded it, and piles of unused salt sat on the roads, spilling over onto a defunct train track. A manual labourer working on road repairs nearby was taking a siesta in the shade of the derelict houses.

“Everybody moved to the city in 2015,” he told me. “There was nobody to buy the salt.” People I met were often curious as to what I was doing, and astonished that I would go it alone. “Danzi zhen da (you’ve got guts),” people would frequently say. “Aren’t you scared?”. “Of what?” I usually asked in return. I didn’t feel like I was being particularly brave. I was just lucky enough to have the time and resources to do a ton of something I loved.

As I drew close to Lanzhou, the capital city that marked the end of my journey, the road to my right began to be framed by the breath-taking snowcapped peaks and peppermint green fields of the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau, and though my legs protested against steeper inclines, I was once again in awe at the variety of terrain I had covered, stopping frequently to catch my breath and admire the view.

By the time I reached Lanzhou, I was exhausted. I had been on the road for more than 30 days; my knees were hurting, my skin had suffered extensively, and the bike needed several things looking at or replacing. What I had gained, however, was a month of almost unbroken joy, new confidence in my ability to conquer formidable distances solo, and a fresh collection of happy places locked safely away in my mind. It’s comforting to know that Gansu’s wild roads will always be there should I wish to return.

WHOS WRITING?

Ellie is a 24-year-old Brit who has spent half her life living in China and hates sitting behind a desk. Her idea of heaven is either on a bike, in a boxing gym, or with a glass of wine and some good company around a campfire

Ellie is a 24-year-old Brit who has spent half her life living in China and hates sitting behind a desk. Her idea of heaven is either on a bike, in a boxing gym, or with a glass of wine and some good company around a campfire