In the AFTERMATH of her divorce, ERICA TERBLANCHE longed to escape into the VASTNESS of the SAHARA. The spartan IMMENSITY of the desert, she says, helped her HEAL in a way nowhere else on Earth could

The greater the darkness, the brighter the stars.” And so too it is in suffering — the greater the sorrow, the greater the opportunity for us to shine — if we choose it. On an ordinary sunny September afternoon, I hit one of the lowest points of my life. My now-ex-wife and I had just stood together at a wooden and barred counter of the High Court in London and filed for divorce.

‘Sign here,’ the clerk said. It seemed so indecent — ending everything as triflingly as buying stamps at the post office. We signed. It was over. Almost seven years. Thousands of miles of adventure.

All the love that had gone before. All the high dreams that once stretched ahead of us and the meaning it gave our lives. All gone.

The divorce papers were filed. On the same day a man-and-a-van came, and it was done. Billy and I went our separate ways. All that remained was the pain, the emptiness, and the flashes of relief — mixed up with grief — and the fragile exhilaration of new freedom, and then again, the loss like a severed limb.

DRAWN TO THE DESERT

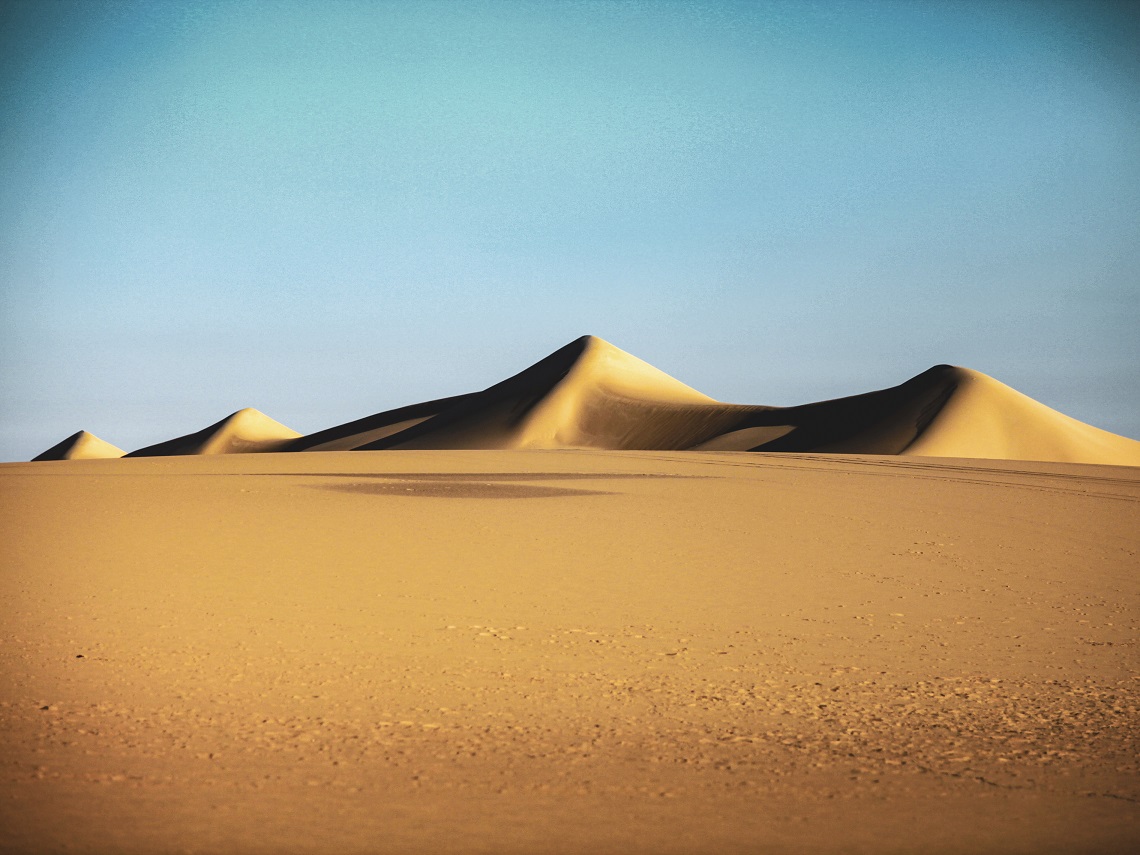

In the aftermath of my divorce, I was compelled towards to the Sahara Desert the way a drowning woman thrashes for the surface. The Sahara I had read about stood out in my mind’s eye as a place of miracles and illumination.

To come through the pain of our divorce, I needed to cut deep, right to my marrow. And one thing was certain, a glossy-brochured camel safari, complete with a train of bearers and a table-buckling buffet for breakfast, lunch, and dinner was not going to it. My heart was clear — I needed to run the Sahara Desert and disappear into all that barren emptiness.

I could never have imagined that I would have an experience so extraordinary; that it would heal my heart in seven short days in a way that seems impossible, even now.

Less than three months after my divorce, I landed in Cairo. I had entered one of the toughest endurance races on the planet, a seven-day run of 155 miles across the Sahara, the hottest desert on Earth. I’d be carrying everything I’d need for the duration of the race on my back — a week’s worth of food, toiletries, a sleeping bag, one change of clothes, two pairs of socks, a hat, a thin foam mattress, a medicine kit, a compass, eating utensils, a headlight, spare batteries, sunscreen, trekking poles, and sandals.

Our race started deep in the heart of the White Desert, a good 250-mile journey from the frenzied hustle and bustle of Cairo. By the time we got to camp, it was past midnight, hours after the intended arrival time. One of the busses had broken down. Racers were tired and hungry. Tensions ran high, and within the hour all had gone to bed.

I sought a quiet moment at the fireside. Three Bedouin men sat in silence, watching the flames and the slow steam rising from a worn metal kettle. There was not a breath of wind. Only stars and stillness.

“Welcome,” said one of the young men and pointed to a low camp seat. “Tea?”

I accepted and we drank in silence. After a while, they introduced themselves as Mohammed, Mahmud, and Hamada. Mahmud had the face of a desert angel after rain, smooth skin, wide mouth, large hazelnut-brown eyes, and the most gracious manner.

I thanked them for the tea. “You’re welcome,”. Mahmud said in a voice so gentle it felt like Rumi was speaking from the star-washed sands. I felt a stirring of love where all my sorrow lived and realised that the Sahara had begun its healing work.

A SURPRISING START

The long wait was over, months of preparation had come to this one single moment in time. The drummers rolled out the final ten seconds — three, two, one. And we were off!

As far as my eyes could see, the Sahara was a vast ocean of yellow sand and patches of shimmering-hot, salt-white rock-beds. By 10 am and just 12 miles into the race, the ambient temperature reached 48C. I shuffled along, disoriented and dizzy from the assault of heat, dazzling light, and my bare skin being cooked alive. By 18 miles, there was not a soul in sight. In every direction stretched endless space, silence, and the great privilege of solitude.

There is a stillness, a simplicity that comes from running in the desert like this; a pervading feeling that there is enough time and enough reason to feel at peace. It was a feeling that had at its base the simplest and deepest happiness. I stood still for a very long time to absorb the silence.

Midway through my reverie, one of the Racing the Planet Land Rovers came roaring out of the distance. When the vehicle drew near, the passenger rolled down the window and hollered, “Erica! What are you doing?! Run! You are the first lady home!” It was Mary Gadams, formidable visionary and owner of Racing the Planet.

I stared after the car as it sped away in the direction of the finish line. “Can’t be,” I thought, but nonetheless, picked up my pace.

I crossed the line in four hours and 43 minutes, first lady home and a solid 15th position overall out of 133 racers. There was the gift of many hours before the others began to arrive. I cherished this quiet time and used it to do slow, soft yoga inside our empty tent, followed by 10 minutes of stilling my mind. Just breathing. Thinking nothing. Just being. “Erica?” Mahmud ducked his head inside the tent. He held out a cup of sweet black tea. “Welcome,” he said and flashed that dazzling smile. I know not why but his presence loosened the tight gauze around my broken heart more than any other person in the race.

One by one, racers came over the finish line and staggered to their tents. Our camp of 15 Bedouin tents were arranged in a semi-circle, each one facing inwards and housing eight racers. Over the next seven days, the people in my tent became closer than family, because we were each in our own way going through a life-changing experience and sharing it intimately in our waking, racing, struggling, eating, and sleeping in such close quarters. In those harsh conditions, the veneer washes away very quickly beneath the sweaty brows. All that remains are our open-hearted selves, without pretence or façade and the great gift of authentic connection.

At sunset, I clambered high up onto one of the white sandstone sentinels that guarded our camp and sat there in the vastness until the sunset golden across the infinite horizon. I waited until the stars emerged one after the other and eventually covered me in a cascade of shimmering diamonds. I sat there long after everyone went to sleep and felt a universe of peace settling over me.

There were still six days of racing ahead of me. Each day in some way or another had some extraordinary quality about it, and each day subtly chiselled away at my heartache. But it would be a sin to rush you through it.

What I can share is that by the time we had run 160 miles and reached the finish line on the 7th day, I had won the race against all odds and my own expectations, and by a staggeringly large margin. The race ended at the foot of the awe-inspiring Pyramids of Giza where, Mary Gadams awarded me an enormous silver Wimbledon-Tennis-sized winner’s plate for first female home.

SOUVENIRS

Within minutes of saying my goodbyes to all my tent mates and my fellow racers I was in a taxi on route to Cairo airport — un-showered, desert-raw, undone from seven days in the wilderness and changed in ways I had not yet fully understood.

On the plane, I took my seat next to a Swedish couple, Clause and Catherine from Gotland. Catherine leaned over and asked about my spectacular trophy. Only then did I burst into tears. I wept and wept – completely stripped of all the layers that conceal us, my heart blown wide open and cleared out.

Onto Catherine and Clause’s laps poured all the grief from losing Billy, all the gratitude for everything that happened in the desert, for the race and the desert itself, and all the love for the Bedouin brothers, and Mahmud — all of which would be in my bones and my soul forever.

I sent Mary Gadams an email of thanks and ended the note with what I learnt from the race: “Don’t run with your legs; don’t run with your arms; don’t run with the limits of your body. The best way yet is to run gently — run with your heart.”

The Sahara race had begun a life-long affair with long-distance running which would enrich my life in ways I could have never foreseen.

Within a week of arriving back in the UK, I had signed up for the Racing the Planet 155-mile race across the Atacama Desert in Peru.

Each high-paced adventure, set in some of the most majestic yet unforgiving landscapes on Earth, transports you to a new continent and right into the thick of it. Available from www.amazon.com

Racing the Sahara was like falling in love for the first time, and no race after would ever quite compare. There was no competitive pressure, nor a benchmark of prior performances to live up to. I was anonymous and had no expectations of myself other than to finish the race — even if it meant I had to walk the entire course. I had no idea what to expect, nor any sense of how profound seven days of running through the desert could be.

For these reasons, running the Sahara in October 2009 remains the purest and most spiritual race I participated in for the next 10 years of competitive endurance running. I would only return to this blissful way of running when I entered my 50s, racing again purely for the joy of it and forgoing entirely any notions of podiums and winning.

American writer, Carlos Castaneda, who famously wrote about his training in shamanism, said, “All paths are the same. They lead nowhere. Does this path have a heart? If it does, the path is good; if it doesn’t, it is of no use. One makes for a joyful journey. The other will make a curse of your life. Look at every path closely and deliberately, and ask, ‘Does this path have a heart?’”

The path was set, and my heart was wholly in it.

WHO’S WRITING?

Erica Terblanche is an accomplished endurance runner and adventure racer who has won numerous iconic long-distance races all over the world. She is an adventurer at heart and has cycled 6,200 miles through South East Asia, hitchhiked from Cape Town to Somalia, and circumvented most of the Greek islands by kayak. Erica is a Life Coach and psychologist with a master’s degree in Positive Psychology. She is also the founder of Thrive Guru and Thrive Run Club, both of which help people live happier, healthier, more fulfilling lives. You can follow Erica on Instagram @ericaterblanche, @thrive_guru, or join her @ThriveRunClubGlobal on Facebook.

Erica Terblanche is an accomplished endurance runner and adventure racer who has won numerous iconic long-distance races all over the world. She is an adventurer at heart and has cycled 6,200 miles through South East Asia, hitchhiked from Cape Town to Somalia, and circumvented most of the Greek islands by kayak. Erica is a Life Coach and psychologist with a master’s degree in Positive Psychology. She is also the founder of Thrive Guru and Thrive Run Club, both of which help people live happier, healthier, more fulfilling lives. You can follow Erica on Instagram @ericaterblanche, @thrive_guru, or join her @ThriveRunClubGlobal on Facebook.