CHASING WHITE WALES

The WEATHER can turn quickly in WILD places, no matter where you are in the world. WHITEOUTS can happen on the Welsh PEAKS just as easily as in the Himalayas, as this pair of hikers found out on the CARNEDDAU RANGE, Snowdonia

The wind felt like needles on my skin. Every time it gusted, shards of ice blew off the ridge and hammered into us. Even through my thick jacket and hiking trousers, I couldn’t stop the hail that drove into me. We popped our hoods and trudged on, staring at the ground.

The wind felt like needles on my skin. Every time it gusted, shards of ice blew off the ridge and hammered into us. Even through my thick jacket and hiking trousers, I couldn’t stop the hail that drove into me. We popped our hoods and trudged on, staring at the ground.

The wind was roaring in my ear and it took me a moment to realise Jack was shouting something at me. I looked up to see his lips moving but no noise came out. Seeing the blank look on my face, he shook my shoulder and pointed up ahead. A thick bank of cloud was flowing down the summit towards us and the looming sky above was ashen. A whiteout.

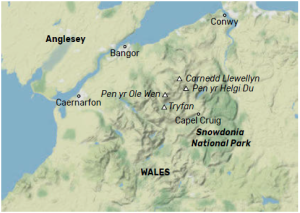

This didn’t happen trekking in the high-Andes or mountaineering in the Himalayas. It occurred on the low peaks of Wales, in Snowdonia National Park. Despite the highest summit in this region, Snowdon, reaching only 1,085m, the weather can be formidable and tempestuous. Storms blow off the Irish Sea at the drop of a hat, coating the peaks in freezing fog, hefty winds, and in our case, snow.

A CHANGE OF PLANS

The day began like any other. I’d driven up to Bangor in North Wales to stay with my university friend, Jack. We had planned on spending a week in the mountains doing some camping and hiking. Jack had just returned from two years in British Columbia, Canada. During the winter he worked as a ski instructor, and during the summer he worked at a rock-climbing gym and as a tour guide at a grizzly bear lodge.

His experience in the mountains was going to come in useful, and we hoped to weave some scrambles and rock climbing into our daily excursions. I’d spent the last year hiking 500 miles of long-distance trails in the UK. These trips included the Pembrokeshire Coast Path, Hadrian’s Wall Path, and the South Downs Way. I’d also done a number of day hikes and wild camping trips around the Peak District, Surrey Hills, Gower Peninsula, and along the Southwest Coast Path.

I was in good shape and ready to take on whatever Snowdonia threw at me, though I lacked experience in one key area. I was predominantly a three-season, low-altitude hiker; I didn’t have knowledge of mountain ascents or dealing with winter conditions such as ice and snow.

This was where I hoped my hiking partnership with Jack would work well as that was exactly what he brought to the table. The night I arrived in Bangor, our plans changed promptly. The weather forecast was predicting temperatures of -7C on Snowdon with nightly snowfall and an even colder wind chill. This all but scuppered our camping plans. We simply didn’t have the equipment to safely stay out in those sub-zero temperatures overnight. Instead, we agreed to tackle two challenging scrambling routes. The first: an ascent up Crib Goch to reach Snowdon. The second: the Carneddau Southern Ridge Circuit, beginning in the Ogwen Valley.

A SOGGY START

The weather was looking better across the Carneddau range with some light snow showers in the morning, so we opted to do that hike first. We sat at Jack’s kitchen table with a steaming cup of tea in one hand and an OS map of Snowdonia rolled out in front of us. Jack flicked through a guidebook of North Wales climbing routes, to get information on the scramble. The toughest section would be the route coming up from Llyn Ogwen. Yet this was still only a Grade I scramble and was classified as a ‘non-technical climb’, meaning it would require the use of both hands and feet to get up it, but no ropes, protection, or special training.

We packed stringently but responsibly. Waterproof trousers and gaiters for moving through the snow. Hats, gloves, and extra layers for the cold conditions. I brought a thermos of coffee and a spare pair of gloves. Jack carried a map, compass, and an emergency blanket for if worst came to the worst.

We both packed snacks — apples and granola bars. “Shame we don’t have any crampons,” Jack said as we climbed into the car. “Yeah well, we’ve got everything else,” I replied. “Let’s hope there’s not a blizzard,” he said. We both laughed. “In Wales?” I replied. “Not a chance.”

We drove south, passing through the town of Bethesda before entering the Nant Ffrancon pass. From here the valley rose above us in a wall of frost-shattered rock before reaching a line of snow that topped all the mountain peaks. We parked our car east of Llyn Ogwen on the roadside before joining the trail leading up to Ffynnon Lloer — a glacial lake resting beneath the Carneddau. We walked slowly at first, limbering up and stretching as we went.

Streams of water were pouring down the valley from the snowmelt. The ground was marshy underfoot and we were forced to meander through patches of bog and alongside crystalline waterfalls. Jack quickly pulled ahead of me, his nimble feet hopping over slippery rocks and clambering up rivers of stone. I lagged behind, breathing heavily, unused to this sort of acrobatic speed-hiking.

I’d chosen to wear trail running shoes, hoping the light footwear would help me skip across the rocks. But as I trod into another sodden patch of land and felt the freezing water soak into my socks, I started to think maybe this wasn’t such a bright idea. Pushing aside thoughts of the problems my soggy socks would cause when we reached the snowline, I picked up the pace, attempting to catch up with Jack and keep myself warm in the process.

THE APPROACH

We arrived at Ffynnon Lloer breathing heavily. We slumped onto a boulder among the straw grass and got out our water bottles. A bitter wind was blowing off the lake and it wasn’t long before we were shivering. I stared upwards. In a few steps, we would enter a monochrome world of snow and ice.

“You ready for this?” Jack grinned at me. I nodded, though I wasn’t sure I felt as confident as he did. “I’m gonna try and carve a route for us up this rock,” he said, pointing. I followed his finger, which traced a line through a scree slope and up an exposed ridge. “When we reach that snowfield, we’ll slip on our gaiters and push on to the first summit. We want to try and do this initial ascent fast to give us time to reach the other peaks before dark.”

I checked my watch. It was mid-morning, plenty of time to complete our intended 10-mile route, although the distance wasn’t the problem. It was the 1,000m of elevation and three peaks we had to climb. We tucked our water bottles back into our bags and were off, like a couple of hares racing through the undergrowth.

As planned, Jack led the way. He kept a low centre of gravity, weaving among the boulders. He flowed between the rocks, keeping three touchpoints close to the ground at all times. I could see his climbing technique coming out. The way he manoeuvred his feet and how he kept his balance using his hands made sure he stayed absolutely in control. I lumbered behind, picking my way through the loose rock. The grass was still slushy, and we were sending sprays of muddy water out in all directions. “Pick your own route along this section,” Jack called out over his shoulder. “Whatever you find most comfortable!”

Everything moved in the scree slope. Fragments of rock spilt away beneath my feet as I trod on them, sending mini avalanches downhill. At this level, the ground was beginning to freeze rapidly and wherever there was grass, it crunched underfoot. There was no longer a track to follow. We were led by pure instinct. In a way, it was like a game of chess. While moving, the trick was to not only watch your feet but continuously plot your path onwards, always staying a few steps ahead.

THE HOVEL

We halted at the base of a gulley, both red-faced and in clouds of breathy fog. “We need to climb this,” Jack said. I looked up. The rock was shaped like a wedge with a crack running down the middle. Snowmelt was coming down one face, but the other was dry and lined with handholds. “Alright, you go first, and I can watch what you do,” I replied.

Not needing a second offer, Jack leapt up the rock. He shimmied up the gap, moving his feet in sync with his hands. It was only a short section and within moments he’d hauled himself up onto a shelf. “Now, you!” He called down to me. I flexed my cold fingers and pushed them against the icy rock. Attempting to set myself into a rhythm, I wedged my feet into the crack and lifted myself up, fumbling for handholds. Testing a loose root, I gave it one last tug before pulling myself onto the platform. Jack let out a whistle. “Some view,” I wheezed, shuffling alongside him.

The rock fell away behind us, down the jumble of scree, across the glittering marshland, before sweeping out over an expanse of yellow grass into the valley. We perched there to have another drink and to clip on our gaiters, but mainly to admire the view. The wind was racing down the ridge towards us, and we decided to get into jackets and pull on our gloves. I headed up first, following the ridge towards the first summit of Pen Yr Ole Wen (978m). After a series of ragged switchbacks, we rounded a bulging snowfield to reach the peak. We sat on the summit marker and had a sip of coffee to celebrate.

Around us, Snowdonia stretched out impressively in all directions. The Ogwen Valley, and numerous other areas in the National Park, have been sculpted by glaciation. Many of the stunning natural formations seen today were carved out by glacial action during the last Ice Age 10,000 years ago. You can feel the presence of the features lining the landscape around you. On the opposing valley wall, Tryfan is the dominant landmark — a rugged ridge also popular with scramblers. To the right, a canyon is scooped out of the rock — Cwm Idwal — the birthplace of a glacier.

To the south, we could make out the Glyders frozen with ice. Behind them, the dark crag of Crib Goch led to the triangular peak of Snowdon which looked like a jagged shark’s tooth from this distance. The wind was beginning to whip around us, and masses of black cloud were drifting through the sky. I pulled up my snood to cover my nose from the windburn and we pushed on, heading for the second peak. “Careful near that edge,” Jack shouted.

I stopped in my tracks and looked to my right. We were on a bluff of snow running northeast towards Carnedd Dafydd. Gusts of wind were striking the ridge horizontally and blowing drifts of sparkling ice into the air. I glanced over the edge and saw what he meant. The snow had folded over causing a false lip to form, much like a crevasse. If I walked too close, it would crumble beneath my feet causing me to plummet a full 300m down a sheer cliff to the black waters of Ffynnon Lloer.

I moved away from the edge and we pressed on. By now, my long-distance hiking endurance was coming into its own and I had taken on the role of leader. It was tough going through the snow. In places, we sank up to our knees and the continuous incline was only making things worse. We didn’t speak as we cut upwards, striving for the summit. Eventually, a mound of stones rose up ahead marking the highest point of Carnedd Dafydd at 1,044m.

The clouds were descending, and visibility was beginning to drop. We could no longer see out across to Anglesey or over to the Llandudno mudflats. Fearing a whiteout was imminent, we made for the storm shelter that was shaped like a figure-eight beside the summit marker. We bundled into the nearest side and crouched down just as a howling wind blasted over us. Not wasting any time, we pulled on our last layers and got out the hot coffee to warm ourselves.

The wind was sucking down into the hollow of the shelter and swirling around the inside like a snow globe. We crouched on the floor, covering our faces and laughing, partly to ease the nerves and partly from genuine excitement. “Our hovel!” I cried out over the wind. Through the gap in the stone, we could see the grey mist rushing past. Not moments before, there had been sun and views for miles all around. It’s easy to see how dangerous these wild areas can be when the weather turns.

The longer we waited, the colder it got. Eventually, the visibility lifted for a moment and we saw a flash of blue sky. Sensing this was our opportunity to make a dash for it, we packed up and made way for our third and final peak.

TO THE SUMMIT

We weren’t 50m from the storm shelter when the wind began to scream again. Jack was in front of me, with his hood tightly wrapped around his head. As he turned to look back, a squall of wind hit him side on, almost sending him sprawling. He dropped towards me just as a thick white fog descended from the peak above us. Neither of us had snow googles and I had resorted to using sunglasses to protect my eyes.

Visibility reduced to a few metres, we were caught between pushing on and making our way painstakingly along the mountain edge or turning back to the safety of the storm shelter. We chose to continue, sticking close together and shuffling forwards as the wind bit viciously at our skin. I stared at my feet sinking into the snow and prayed the visibility would lift soon. A landscape that seems so familiar can suddenly become disorientating and truly foreboding in a whiteout. But as fast as it came, it was gone.

I realised the wind had eased off and I could hear the crunch of our footfall again. I looked up to see the brilliant white peak of Carnedd Llewelyn (1,064m) basking in the sunshine. We turned down our hoods and wiped the sweat from our eyes. The valley opened up once more as we mounted a long, steady climb to the peak, zig-zagging back and forth through the snow, coats steaming.

Once at the top, we high-fived and dropped into another storm shelter to rest. Again, the wind was squalling, but this time the visibility was clear. We were out of coffee and low on water. We ate the last of our snacks and looked at each other.

“No blizzard, huh?” Jack said.

“I wouldn’t call that a blizzard,” he said.

“Well, whatever it was, it got hairy back there for a second.”

“I wouldn’t have it any other way,” I said.

We looked at each other and grinned. “No, me neither,” Jack replied. And with that, we began our descent.

WHO’S WRITING?

Matt is a freelance travel writer and filmmaker specialising in outdoor adventures. His travels have taken him trekking in the Himalayas, backpacking through Asia on the Trans Siberian Railway, and wild camping along 500 miles of long-distance hiking trails in the United Kingdom. Follow his adventures now at mattwalkwild.com.

Matt is a freelance travel writer and filmmaker specialising in outdoor adventures. His travels have taken him trekking in the Himalayas, backpacking through Asia on the Trans Siberian Railway, and wild camping along 500 miles of long-distance hiking trails in the United Kingdom. Follow his adventures now at mattwalkwild.com.