GREAT SCOTT

At the end of last year, the world said GOODBYE to one of the GREATEST mountaineers of our time. A teacher, philanthropist, and pioneer, DOUG SCOTT will forever be remembered as an INSPIRATIONAL climber who knew no limits. Here, we pay TRIBUTE to his life, his climbs, and his truly UNBREAKABLE spirit.

Doug Scott was one of the world’s most successful mountaineers of the modern era. He sadly died of cerebral lymphoma, a form of brain cancer, on 7 December 2020, aged 79. Doug was a prolific climber, cataloguing hundreds of peaks all around the world, many of them with new routes. In total, he made 45 expeditions to the high mountains of Asia. Doug is probably best known for being the first to climb the Southwest face of Everest, along with his groundbreaking climbs on the Ogre and Kanchenjunga.

Doug pioneered the idea of lightweight, alpine expeditions when climbing the world’s highest peaks without the use of bottled oxygen. He was also the founder of Community Action Nepal, a charity whose aim is to improve the lives of people in rural Nepal.

EARLY YEARS

Doug was born on 29 May 1941 in Nottingham, England, the eldest of three sons to Edith and George Scott. Doug’s parents were always keen to introduce their children to the delights of the great outdoors, particularly within the nearby Peak District. Doug’s mother was a supervisor in a cigarette factory and his father was a police officer and an amateur boxer, who in 1945, became the British Amateur Heavyweight Champion. As children, the three brothers spent much of their time exploring their local surroundings and building dens. Doug was a restless child in school and found it difficult to concentrate, which meant he didn’t enjoy much of his early education.

In 1953, when Doug was 12 years old, he witnessed a life-changing event while out walking with the scouts. As the group trekked among the hills of the Peak District, they came upon a group of people who were out rock climbing on a crag called Black Rocks. Watching the climbers scale the gritstone outcrop made a definite impression on Doug. Consequently, two weeks later, Doug along with two friends, cycled 25 miles from his home in Nottingham back to that very same crag. The aim of this visit was to sample rock climbing for themselves using a washing line Doug had liberated from his mother’s garden.

He later wrote, ‘We slithered and slipped, grazing our bare legs, but managed to climb the easier chimneys.’ Doug was instantly hooked, and so began regular walking and climbing trips to the Peak District. Day visits turned into weekends, gaining valuable climbing experience while steadily accumulating better climbing gear, including a nylon rope. As Doug plodded through his secondary modern school education, he suddenly realised that, without any academic qualifications, he was destined for a life working down the local coal mines.

This was a wake-up call for young Doug and he began to work a little harder in school. He soon discovered a love of reading and moved to a local grammar school, which led him to teacher training at Loughborough. Throughout the remainder of the 1950s, Doug continued climbing, gaining experience and honing his skills. He began travelling further afield, taking on challenging routes in the Lake District and Snowdonia along with winter outings to the Highlands of Scotland. Doug was steadily becoming a gifted climber. In 1958, aged just 17, only five years after starting climbing, Doug completed his first Alpine season.

CLIMBING FURTHER AFIELD

Over the next few years, he climbed numerous challenging routes throughout the Alps. In Morocco in 1962, Doug made the first ascents of routes on Toubkal, the highest peak in the Atlas Mountains. Three years later, he travelled to the Tibesti Mountains of Chad where he made two new first ascents on Tarso Tieroko. This North African jaunt was with seven friends who travelled overland across the Sahara in two ex-military trucks.

The following year Doug led a group of 20 young people from Nottingham schools on an expedition to Kurdistan based on the Turkish/Iraqi border. Once there, they made a number of first ascents on Cilo Dagi. These latest journeys were more than mere mountaineering adventures. According to Doug, his desire was also, ‘driven along by curiosity to see and experience the different lands and people in them as much as to climb the mountains.’

The following year, Doug travelled once again overland, to the Hindu Kush in Afghanistan where, among a number of successful ascents during the expedition, Doug made the first ascent of the South Face of Koh-i-Bandaka.

From the late 1960s onwards, Doug’s climbing soared to new heights. He was taking on more challenging routes with a growing fondness for climbs with big walls and exposed overhangs. These included technical cliff climbs on the Isle of Harris and on the Bonatti Pillar in the French Alps. In 1970, Doug climbed several routes on the big walls of the Yosemite, USA. These included the first European ascent of Salathé Wall with the Austrian, Peter Habeler.

There were also trips to Troll Wall in Norway and to the Tozal del Mallo region in the Pyrenees. Doug even managed to fit in a trip to Baffin Island where he made the first winter ascent of Killabuk. With his long hair, beard, bandana, and round glasses he was occasionally mistaken for the Beatles’ John Lennon while out climbing! Doug stopped teaching at his secondary school in Nottingham when it became increasingly difficult for him to get time off for his numerous expeditions.

In 1972, there was a real breakthrough in his climbing career when Doug was invited to climb Everest’s South-West Face. This was an international expedition led by the German climber Karl Herrligkoffer. Although the attempt to reach the summit failed, Doug had finally discovered his climbing niche. His superb performance during the climb was widely acknowledged and whet his appetite for more high altitude challenges.

Just months later, he returned to the region as part of an attempt on the same face of Everest, this time led by Chris Bonington. Once again, Doug had a successful trip, reaching 8,300m before the on-coming monsoon weather put pay to any further climbing. In 1972, Doug also made the first ascent of the east pillar of Mount Asgard on Baffin Island.

The following year, he climbed another classic Yosemite wall, 880m of ‘The Nose’, on El Capitan. In 1974, Doug returned to the Himalayas as part of an Indo-British team attempting to climb the perfectly shaped granite peak of Changabang in northern India. The climb was a resounding success and another first ascent. After which, he went on to complete the first ascent of the Southeast ridge of Pik Lenin in central Asia’s Pamir Mountains.

MOUNT EVEREST AND THE OGRE

In 1975, Doug was invited on the large Everest Southwest Face Expedition. He was an obvious person to ask as his skills and drive to succeed were extraordinary. As he had already anticipated, climbing the Southwest Face would be a very challenging undertaking for expedition members. Doug and his partner, Dougal Haston, eventually established the highest camp on the mountain.

They left there at dawn to climb the couloir to the South Summit which they eventually reached. Although it was late in the day, the pair made a decision to continue upwards, finally topping out on the North Summit of Mount Everest. Doug and Dougal were ecstatic. They had become the first Britons to climb the mountain. Later Doug commented: ‘Clouds were forming and billowing out of the valleys down there in Nepal. Standing there, it felt as though you were part of something much bigger than yourself.’

There, they remained for an hour before starting their descent in fading light. Around 100m below the summit, the climbers made a decision to stop. With effort, they dug a snow hole and crawled inside, to lessen their exposure to the wind. Sitting on their rucksacks the pair tried to keep warm by rubbing their extremities and placing cold toes under each other’s armpits. With their torches dead and oxygen cylinders empty, they just waited for the sun to rise.

At the time, it was the highest bivouac in mountaineering history. Doug was amazed that it was possible to survive without oxygen, a sleeping bag, or down clothing, at a temperature of – 40C without suffering frostbite. This was a key discovery and a turning point for him and other climbers to consider for future expeditions.

Could such high mountains be climbed without the use of oxygen? For Doug, expeditions using fewer climbers were now also on the cards. Perhaps small, lightweight teams were the future? The following year, these same two climbers made a lightweight Alpine-style ascent of Alaska’s Denali.

In 1977 Doug was back in the Himalayas again, this time joining a small team attempting Baintha Brakk, also known as The Ogre. The ascent involved some exceedingly technical climbing at very high altitude. It went well with Doug and Chris Bonington reaching the summit. While abseiling down a gully after leaving the top, Doug’s foot slipped on an icy wall. It resulted in Doug swinging like a pendulum on his rope before breaking both legs as he smashed into rock. With only two of them high up on a Himalayan mountain, Doug and Chris found themselves in a desperate situation. Remarkably, Doug was able to abseil.

With a great deal of help from fellow expedition climbers Mo Antoine and Clive Rowland, who joined them from a lower camp, they eventually returned to Base Camp. This remarkable descent involved eight days of sliding and crawling on all fours without food or painkillers. Chris Bonington also suffered broken ribs on the descent, which resulted in him having his own problems. The episode has to be one of the most epic descents in mountaineering history. Afterwards, Chris commented: “I don’t think anyone except Doug would have had the physical and mental strength to make it down the mountain with two broken legs.”

FURTHER CLIMBS

Between 1978-2000, Doug went on to visit many more of the Himalayan giants – his stamina and ambition were relentless for high altitude adventure. With his new belief that such huge peaks could be climbed using smaller lightweight parties, he was keen to take part in smaller expeditions. After Everest, all his Himalayan climbs were completed in lightweight, Alpine-style and without bottled oxygen. His many successes were impressive: Nuptse and Kanchenjunga in Nepal; Shivling in India; Broad Peak in Pakistan and Shishapangma in China, are but a few of the Himalayan mountains he climbed during this period. Indeed, the entire list is long!

His ascent of Kanchenjunga in 1979, which he climbed with Joe Tasker and Peter Boardman, was of particular significance. Tackling the mountain by its North Ridge, it presented a superb opportunity for lightweight alpine style climbing. On their third attempt at summiting, they climbed to the North Col, then along the North Ridge to the pyramid summit. It was a success, only the mountain’s third-ever ascent and the first by its North Ridge. Reflecting on the climb afterwards, Doug said, “We pulled it off against all the odds….the most demanding climb I ever did…the first time a big mountain had been climbed lightweight, without masses of fixed ropes, without a lot of Sherpa support.”

There were other expeditions where, for a variety of reasons, Doug was unable to summit. They included K2, Makalu, and Nanga Parbat which were all attempted, sometimes on a number of occasions and with strong teams.

However, these attempts were abandoned because of high winds, heavy snowfall, illness of fellow climbers or problems with the local officials. Such difficulties were part of the very nature of climbing such huge and complex mountains in remote regions.

An interesting aspect of Doug’s climbing philosophy was that he didn’t care to get to the top of a mountain just for its own sake. Doug wasn’t always keen on the regular routes up a peak, preferring to take a new line and more interesting challenge. It was that unknown element that he found to be more of an attraction, once stating, “Climbing is about pioneering new routes, exploring new ground, facing the unknown.”

In between launching expeditions to the Himalayas, Doug would also venture off to other areas of the world to tackle new climbs. He visited Jordan, Canada, Terra del Fuago, Australia as well the European Alps. Furthermore, he didn’t neglect the British scene where he still found time to create new climbing routes.

As Chris Bonington, once said of Doug, “I have never known anyone with such an appetite for climbing.”

Included in his list of locations was the journey to Antarctica in 1992. There, he climbed Mount Vinson at 4,897m, the highest point in Antarctica. Doug also climbed a new route on the North Face of Carstensz Pyramid at 4,884m in Indonesia. This significant climbing achievement saw him join the exclusive ‘Seven Summits’ group, those who had managed to climb to the highest point on all seven continents.

This achievement isn’t often recognised in Doug’s extensive roll-call of successes, but to have completed the Seven Summits is a phenomenal mountaineering accomplishment.

DOUG’S LATER YEARS

In 1989 Doug Scott founded the charity ‘Community Action Nepal’ (CAN). After having climbed throughout the region for many years, he had come to appreciate the people living in these remote regions of Nepal. The local people from villages, where it is difficult to make a living, work so hard for foreigners to obtain their dreams. Doug believed it was incumbent for those from richer nations who visited the mountains, to give something back.

Community Action Nepal

CAN works closely with local communities to improve living facilities in rural regions of Nepal, including children’s education, health provisions, clean water, crop-growing, and building shelters.

For more, see www.canepal.org.uk

CAN now works closely with local communities to improve living facilities in these rural regions. There are around 60 projects to date, which include improvements in the education of young people, developing better health facilities, providing clean water, growing new and more effective crops, and building life-saving shelters for porters on trekking routes. CAN has also been involved in Nepal’s reconstruction after the 2015 earthquake. The charity has helped more than 250,000 people living in Nepal.

Doug was also behind the development of Community Action Treks (CAT), a non-profit organisation with a strong ‘responsible tourism’ ethos. The group organises treks across the Himalayan region with a view to providing resources for the areas where trekking takes place. After his cancer diagnosis in March 2020, Doug still found time during the first national lockdown to raise funds for CAN by walking, with some difficulty, up and down his stairs at home. Ascending and descending his stairs many times, was to raise funds for medicines, equipment, and masks during Nepal’s coronavirus outbreak.

Over recent times, Doug was involved with many aspects of mountaineering development: he was BMC vice-president, the chair of the Mount Everest Foundation and president of the Alpine Club. Doug was honoured with a CBE in 1994. And in 2011, a huge mountaineering award fell to Doug when he became the third-ever recipient of the Piolet d’Or (Golden Ice Axe). This prestigious French trophy was presented to Doug in recognition of his ideals of high altitude climbing. ‘Doug Scott personifies mountaineering adventure and exploration on summits the world over…’ so said the citation. This unique award was also in recognition of Doug’s charity work in supporting the local Nepalese people in their mountain villages.

Doug Scott was one of the most gifted and respected mountaineers of recent times and has made a substantial mark on mountaineering history. From his early days climbing on Peak District crags, Doug travelled a considerable distance, to eventually climb the highest mountains all around the world. His phenomenal climbing record, over so many decades, has been pure inspiration for many fellow climbers and adventurers. What is certain, Doug’s extraordinary exploits will be warmly remembered for many, many years to come.

WHO’S WRITING?

Roger Bunyan has been contributing to Adventure Travel magazine for many years.

Roger Bunyan has been contributing to Adventure Travel magazine for many years.

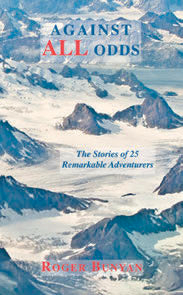

Always fascinating, insightful, and entertaining, it was only natural that the stories of these adventurers were compiled into a book.

Against All Odds: The Stories of 25 Remarkable Adventurers is Roger’s first book and in it he takes a more in-depth look at the adventurers he writes about in each issue of this mag.

The amount of time effort and research that he has put in is astounding, and it makes for captivating reading. To get your copy, head on over to www.hayloft.eu.