The story of a Doctor and a Farmer; the unlikely 18th-century pairing who became the first people to summit Mont Blanc (4,807m)

WHO WERE THEY?

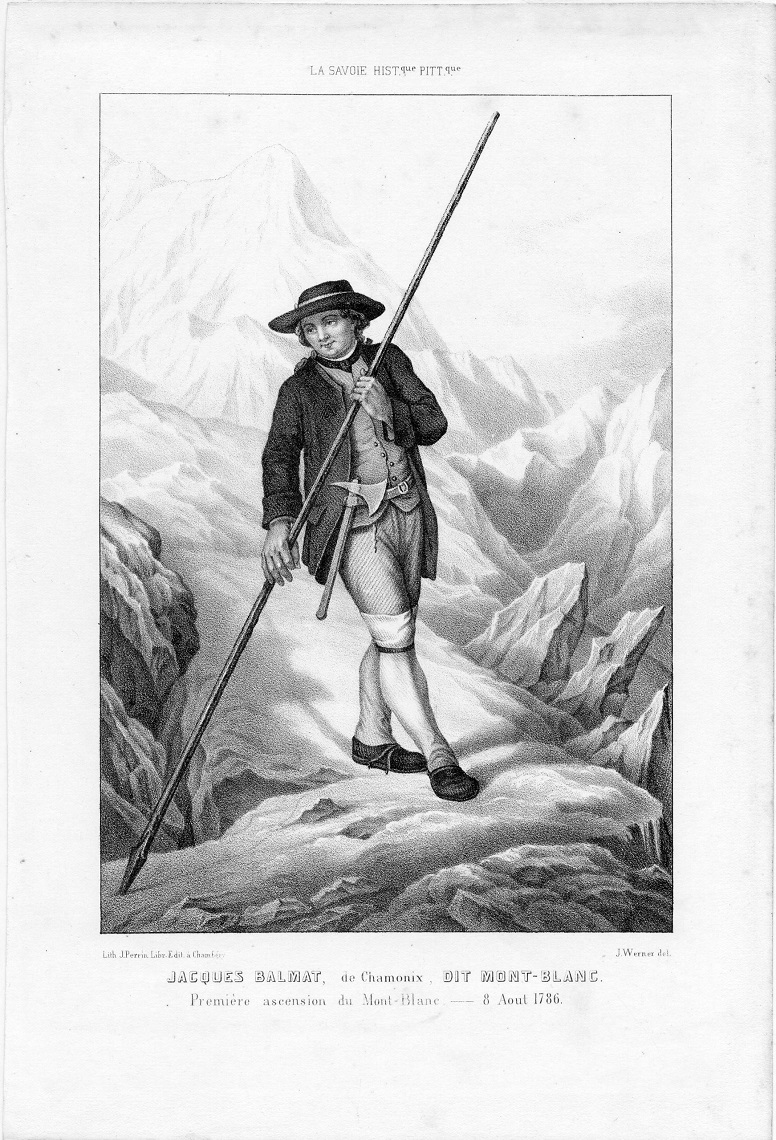

In 1786, Michel-Gabriel Paccard and Jacques Balmat were the first people to climb Mont Blanc (4,807m), the highest mountain in the Alps and Western Europe.

THEIR EARLY LIVES

Michel-Gabriel was born in 1757 in Chamonix in the French Alps. He studied medicine in Turin and Paris before returning to Chamonix as a doctor. Michel-Gabriel was a modest character, energetic, with an ambition to climb Mont Blanc. By 1775, he was making numerous excursions onto the mountain. He primarily viewed mountains in scientific terms and longed to be the first person to take instrument readings from Mont Blanc’s summit.

Jacques on the other hand was from a more humble background. He was born in 1762 on a traditional alpine farm. Jacques became a crystal and chamois hunter, adept at scrambling around the rocky landscape and crossing glaciers. During this period, Horace Bénédict du Saussure, a scientist and alpine explorer from Geneva, visited Chamonix. He became obsessed with Mont Blanc and offered a reward to the first person who successfully climbed it. This was of immediate interest to Jacques, who was always keen to make money.

THE FIRST ASCENT OF MONT BLANC

For centuries, mountains had been regarded as the domain of evil spirits; Mont Blanc was so feared it became known as the ‘accursed mountain.’ A handful of adventurous individuals had climbed to new heights on Mont Blanc, but had so far been foiled by a range of difficult mountain conditions.

After one such trip, Jacques was so badly sunburnt that he went to visit Dr Michel-Gabriel Paccard. The two men discussed their experiences on Mont Blanc and agreed to join forces in a bid to become the first people to climb to its summit. They made an unlikely partnership: one wishing to be the first to take scientific readings from the top; the other wanting to claim the Swiss man’s reward.

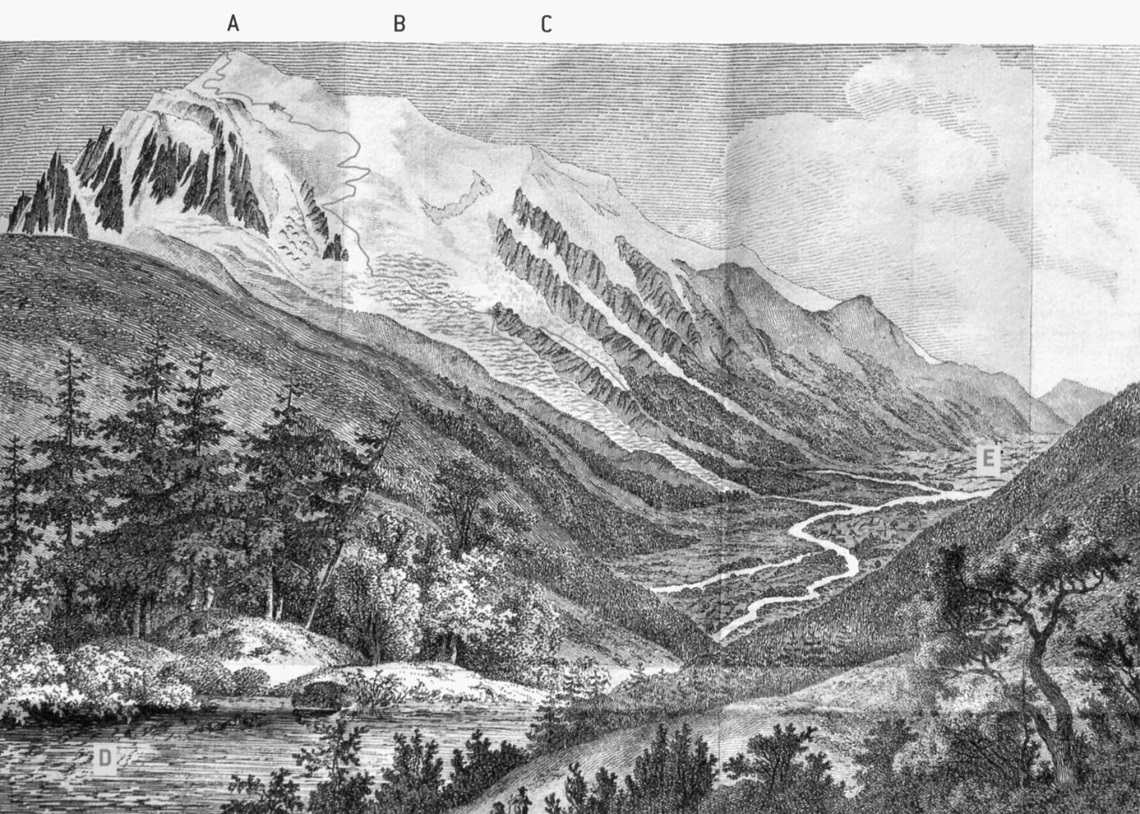

On August 7, 1786, Michel-Gabriel and Jacques began their journey. There were so many unknowns to hinder upward progress: weather conditions, the state of the snow, dangerous crevasses, selecting a suitable route, as well as coping with the altitude. All this to consider while using very basic 18th-Century equipment!

The men wore homespun jackets and trousers and carried one blanket between them. They took a little food and Michel-Gabriel’s rudimentary scientific instruments. They both carried a 2.5m-long baton, a wooden pole with an iron spike at one end. The baton was particularly useful when travelling across glaciers and probing for crevasses.

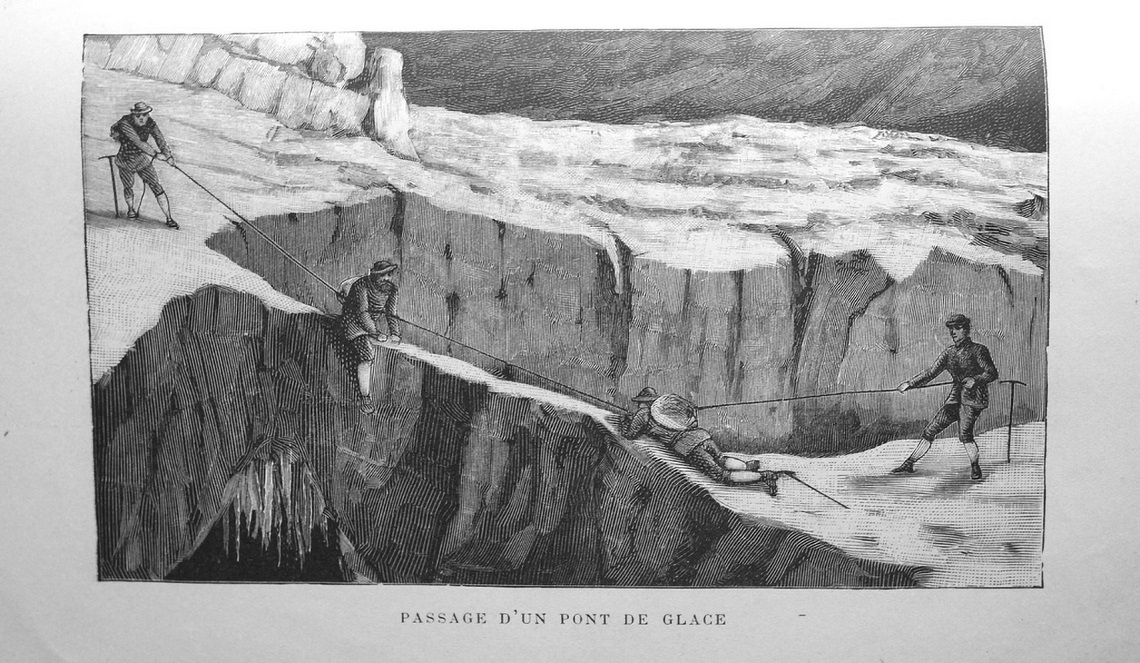

From Chamonix, they made their way up the Montagne de la Côte, where they spent the night under a granite boulder at an altitude of around 2,500m. They left there at 4 am and began their journey across the Glacier des Bossons. The weather was settled, but many of the snow bridges across the crevasses had melted. This required some delicate route finding through a maze of steep ice and gaping crevasses. Michel-Gabriel wrote: ‘Four times the snow bridges, by which we tried to cross the crevasses, gave way beneath our feet, and we saw the abyss below us. But we escaped a catastrophe by throwing ourselves flat on our batons laid horizontally on the snow, and then, placing our two batons side by side, we slid along them until we were across the crevasse.’

It took eight hours to find a way through the glacial ice to the rocky outcrop of the Grands Mulets at just over 3,000m. Jacques became exceedingly tired, struggling with both heat and altitude. Michel-Gabriel kept urging him on and had taken his pack to carry.

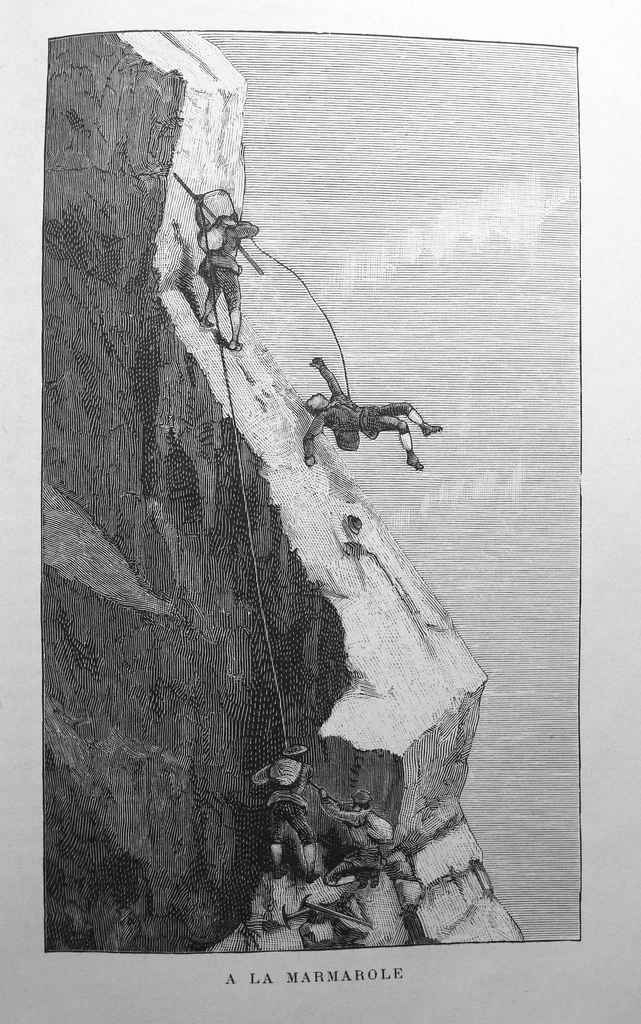

The pair kept going, making their way across Le Grand Plateau. They took it in turns to lead through the snow and avoid falling into crevasses. They were continually blinded by the glare of the sun reflecting from the snow. By 5 pm, they were above the Rochers Rouges, at around 4,550m, where they then met the steepest and most exposed section of the ascent. The snow became very hard and footholds had to be made by using their baton points.

Michel-Gabriel wrote: ‘We had to stop every hundred steps…to regain breath and strength…the higher we got…every fourteen paces.’

It was a remarkable pioneering feat, but Michel-Gabriel and Jacques continued until they reached the top.

ON THE SUMMIT

They stepped onto the summit of Mont Blanc at around 6:30 pm, an altitude of 4,877m. They had become the first people to climb to the highest point in the Alps! Michel-Gabriel attempted to carry out a few scientific observations by taking thermometer and barometer readings. However, he found the process almost impossible as he was tired, cold, hungry, and feeling the effects of altitude. His hands were frostbitten and his eyes were swollen due to the continual glare of the sun.

Jacques spent time waving towards Chamonix in a hope that he would be seen by those following their progress by telescope. After half an hour on the summit, the men began to descend. With two-and-a-half hours of daylight left they moved as quickly as they could. Fortunately, as the sun went down, a bright moon appeared to help light their way.

The temperature then dropped allowing the snow to harden, making the crossing of snow bridges easier. At around midnight, the pair reached the top of the Montagne de la Côte again, after having been on the move for 20 hours. Exhausted and physically suffering, they wrapped themselves in their one blanket and attempted to rest as they shivered in their cold bivouac. The following morning, they continued down the mountainside, by which time Michel-Gabriel was almost completely snow-blind.

AFTER THE CLIMB

Word soon spread of their historic ascent. Jacques travelled to Geneva to inform Horace Bénédict de Saussure that Mont Blanc had been climbed. He was dually presented with his reward. Michel-Gabriel had no interest in receiving a prize. He was content in having been the first to take scientific readings from the summit.

Marc Bourrit, who also lived in Geneva, listened to Jacques’ account of their ascent of Mont Blanc. Marc was a well-known artist and writer about the Alps. He himself had made earlier attempts to climb Mont Blanc. On hearing this news, Marc became extremely jealous of Michel-Gabriel’s success, who was an old adversary. He believed that he should have had the glory of being the first to the summit, not the Chamonix doctor.

In only a short time, Marc managed to transform the entire story. He strongly suggested that such a daring ascent must have been all down to Jacques Balmat. In his version, Michel-Gabriel was the weaker of the pair, requiring a great deal of help to get to the top. Jacques had to continually stop to physically drag the doctor upwards — at one point, Michel-Gabriel had been crawling on all fours, he said. This altered version of the story painted the doctor as a helpless, buffoon-like character. In truth, Jacques preferred this new version of their ascent which made him out to be quite the hero. Sadly, the climbing of Mont Blanc had gone to Jacques’ head.

On learning about the altered account of their ascent, Michel-Gabriel became very upset. However, with Marc being such a well-known and established authority on the Alps, the majority of people accepted this version of events as fact. It was first published in newspapers and then made into a book.

In addition to de Saussure’s prize money, Jacques Balmat was also awarded a gratuity from King Victor Armadeus III, who at that time ruled the Chamonix region. The king also gave him the honorary title of Balmat du Mont Blanc. From monies he was awarded, Jacques eventually built a new chalet in Chamonix for his family and was employed as an official guide of Mont Blanc. Jacques eventually gave up guiding and went off to search for gold in the nearby Sixt Valley. In 1834, Jacques Balmat died after falling from a cliff while mining.

As for Michel-Gabriel, he continued working as a physician in Chamonix and made several more journeys into the mountains over the years. He died in 1827, still unrecognised as having played an equal role in climbing Mont Blanc during its first ascent.

RECOGNITION

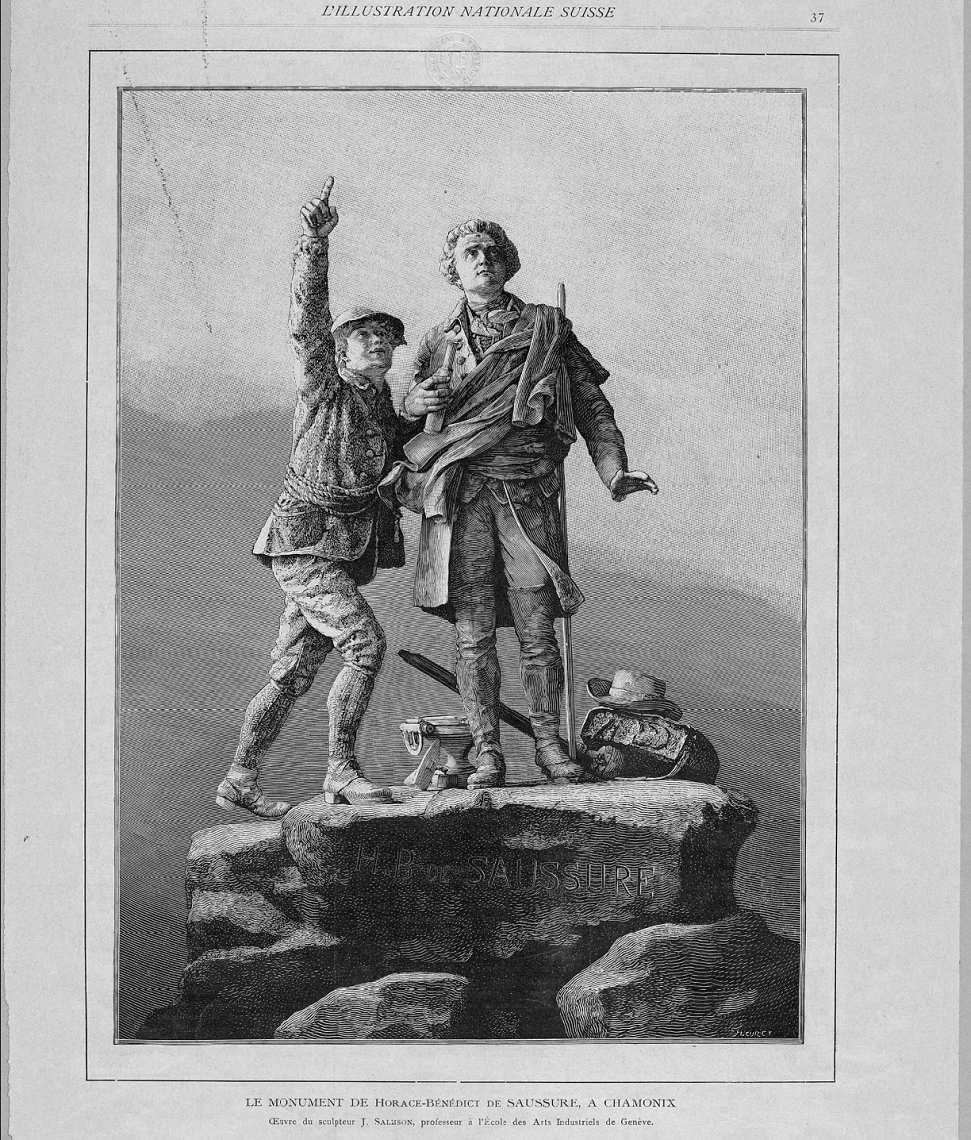

One hundred years after the first ascent of Mont Blanc in 1887, a statue was erected in Chamonix. It featured Jacques Balmat pointing to the summit of Mont Blanc with Horace Bénédict de Saussure looking up. Sadly, Michel-Gabriel was absent from the statue, having been all but written out of the story.

Throughout the 1800s and into the next century, Jacques continued to be regarded as the hero of the ascent. However, after considerable investigation, a wholly different narrative gradually came to light.

It became clear that Michel-Gabriel and Jacques had in fact worked together as equals during their quest. This entirely different story has now been accepted as the true version. In order to correct such an injustice, in 1986, 200 years after the climb, a statue of Michel-Gabriel was also erected in Chamonix. This additional monument is situated 150m away from the Balmat/du Saussure statue.

Although such acrimony was part of the story of the first ascent of Mont Blanc, it shouldn’t lessen the importance of such a milestone in mountaineering history. The two pioneering climbers, who used nothing more than an iron-tipped pole to make their way on an unknown route exposed to cold, altitude, sun-glare, and extremely dangerous slopes. The first ascent of Mont Blanc triggered a positive interest in mountains and heralding the beginning of modern-day mountaineering.

WHO’S WRITING?

Roger Bunyan has been contributing to Adventure Travel magazine for many years. Always fascinating, insightful, and entertaining, it was only natural that the stories of these adventurers were compiled into a book. Against All Odds: The Stories of 25 Remarkable Adventurers is Roger’s first Book, and in it he takes a more in-depth look at the adventurers he writes about in each issue of this mag. The amount of time, effort, and research that he has put in is astounding, and it makes for captivating reading. To get your copy, head on over to www.hayloft.eu.

Roger Bunyan has been contributing to Adventure Travel magazine for many years. Always fascinating, insightful, and entertaining, it was only natural that the stories of these adventurers were compiled into a book. Against All Odds: The Stories of 25 Remarkable Adventurers is Roger’s first Book, and in it he takes a more in-depth look at the adventurers he writes about in each issue of this mag. The amount of time, effort, and research that he has put in is astounding, and it makes for captivating reading. To get your copy, head on over to www.hayloft.eu.