Forget Santa and his reindeer. Meet the Arctic explorer who journeyed over 19,000 miles by dog-sled

WHO WAS HE?

Knud Rasmussen was a Greenlandic-Dane who explored the Arctic during the first part of the last century. He travelled across Inuit lands researching and documenting the Inuit language and traditions. Rasmussen is famous for completing the longest single journey ever made by dog-sled.

EARLY YEARS

Knud Rasmussen was born in 1879 in Ilulissat, Western Greenland. He had a Danish missionary father and an Inuit-Danish mother. From an early age, Rasmussen loved listening to traditional Inuit stories. Like all other Greenland children, Rasmussen learnt how to hunt, drive dog-sleds, and how to survive the harsh Arctic environment. When Rasmussen was 12, he went to boarding school in Denmark. After his schooling, he tried his hand at acting and opera singing before turning to journalism.

RETURNING TO GREENLAND

In 1902, Rasmussen was invited on a Danish Literary Expedition. Its aim was to travel across Greenland and study Inuit culture. The team picked up sleds, dogs and polar clothing in Rasmussen’s old home in Ilulissat before travelling to Upernavik; the then most northerly point of Greenland governed by Denmark.

Here, the team over-wintered until the spring. Once spring arrived, the group travelled across the frozen sea ice of Melville Bay. Eventually, they came across abandoned settlements made by the remote Polar Inuit living in the far north. They ceremoniously raised a flag, declaring that region for Denmark. Over the following months, the expedition members lived with the northern Inuit, hunting with them, sharing food, and learning about their way of life.

In 1905, Rasmussen journeyed to Greenland again and took another long dog-sled trip to visit the Inuit in the far north. He returned to the area again in 1908, crossing the ice to Canada’s Ellesmere Island. Rasmussen hunted and collected hundreds of furs while in Canada, which he took back to Greenland as part of a new venture. Returning to Copenhagen, Rasmussen married talented Danish pianist, Dagmar Anderson.

THE FIRST THULE EXPEDITIONS

A short time later, Rasmussen returned to Greenland while Dagmar remained in Denmark. In a move to open up the north of Greenland to the rest of the world, Rasmussen and his Danish friend, Peter Freuchen, planned to establish a trading post at a location they named Thule in the northwest of the island.

It was a way of securing the region for Denmark as well as providing for the local people. Thule also became a base for future expeditions across the Arctic.

In April 1912, Rasmussen and Peter along with two local men, Uvdoriaq and Inukitsoq, set off on the first Thule expedition, a 600-mile sled journey to north-eastern Peary Land. They wanted to find out if Peary Land was an island separated from the rest of Greenland.

The expedition included four sleds, 53 dogs, and a mass of supplies. They kept to the northwest coast before turning eastwards across the glacial interior. Reaching a height of over 2,000m where temperatures dropped to -30C, their journey posed considerable challenges.

Rasmussen remarked, ‘I see only the white desert, the glacier, which draws in deathly cold and blinding snowstorms.… Hour after hour without hearing any sound, without seeing any living thing.’

After days on the ice, the sleds eventually began to descend the dangerously steep slopes. They continued their journey by following the coast in a northerly direction. The party concluded that Peary Land was in fact part of Greenland and not a separate island. Their return journey was another difficult undertaking, crossing the Greenland icecap once again. The four men suffered a variety of injuries, some of the dogs died, and the food supplies all but ran out. Eventually, they returned after five long months. The double-crossing of the Greenland icecap in the far north had never been achieved before.

News of their success gradually spread across Greenland and Denmark. Time back in Denmark was taken up by Rasmussen writing about the expedition, planning further ventures from Thule, and of course, spending time with his family. Rasmussen eventually had three children with his wife, although he had several other relationships throughout his life, especially with Inuit women.

It was time to return to Greenland, and in April 1917, the second Thule expedition was launched. Its aim was to make further explorations into the far north of Greenland. This second expedition followed the coast northwards where new Arctic locations were discovered and the scientists in the group conducted various studies. Running short on food, the party faced daily challenges as they travelled over the 1,200m-high icecap. The dogs and humans struggled hauling the sleds over the icy and uneven terrain and there were several casualties: one expedition member was suspected of being killed by wolves and another died from the extreme Arctic conditions.

The third and fourth Thule expeditions took place between 1919-1920. The former involved depositing supplies at various locations in preparation for an Arctic expedition organised by explorer, Roald Amundsen; the latter saw Rasmussen travelling to remote and rarely visited Eastern Greenland, to meet with local Inuit people, again gathering more information about Inuit culture.

THE FIFTH THULE EXPEDITION

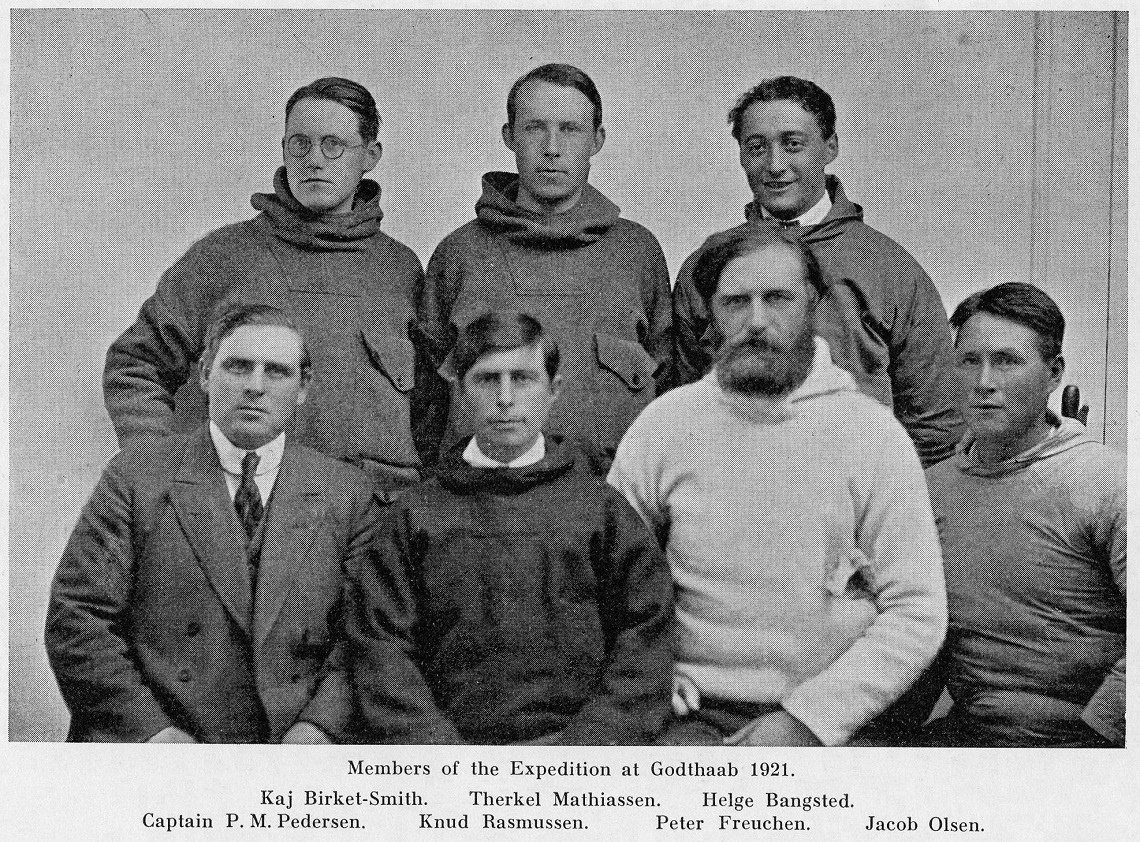

In 1921, expedition members gathered for the fifth Thule expedition, an investigation into the Inuit living further to the west, in Northern Canada, Alaska, and Siberia.

From the Greenland shores, they made their way by ship westward across the Davis Strait and onto the Hudson Strait. The party disembarked on an uninhabited island now called Danish Island. Some members constructed the expedition base while Rasmussen went off to explore this new Arctic land.

He wrote, ‘I had often imagined the first meeting with the [Inuit] of the American Continent….I realised that it had come.’

After scanning the horizon he could make out a line of sleds, so Rasmussen hastily urged his dogs towards them.

‘I had yelled at the dogs in the language of the Greenland Inuit. And, from the expression on one stranger’s face, I realised that he had understood what I said….they went wild with delight…’ Rasmussen was overjoyed that the new people could speak the Inuit language, albeit with a different accent.

Different members of the expedition were divided up and assigned tasks to carry out across the region. A key aim was to investigate the housing, clothing, cooking methods, hunting techniques, and tools the locals used. Of particular interest to Rasmussen were the songs, dances, stories, and ceremonies these Inuit had; he wanted to use these as a way of establishing their origins.

Different Inuit groups were met during numerous sled trips carried out in often very extreme Arctic weather. Once contact had been made, Rasmussen’s party would stay with them for a few days, to learn more about their lives. After 18 months, the first part of the expedition came to a close; around 32,000 artefacts were packed up to be shipped to Copenhagen. Most of the expedition then left the region on their way back to Greenland and Denmark.

However, the second part of the expedition was about to begin. In order to investigate the Inuit living even further to the west, three members planned to make a journey by dog-sled right across the rest of Arctic North America. They intended to sled the length of the North-West Passage, a journey which had never before been achieved.

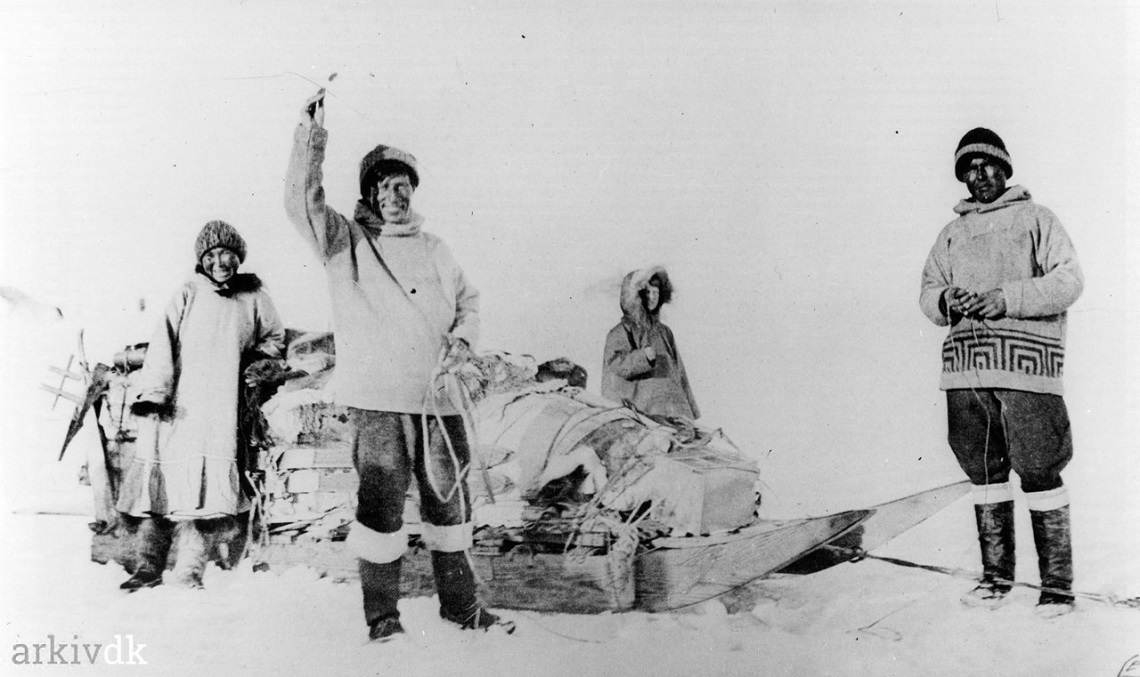

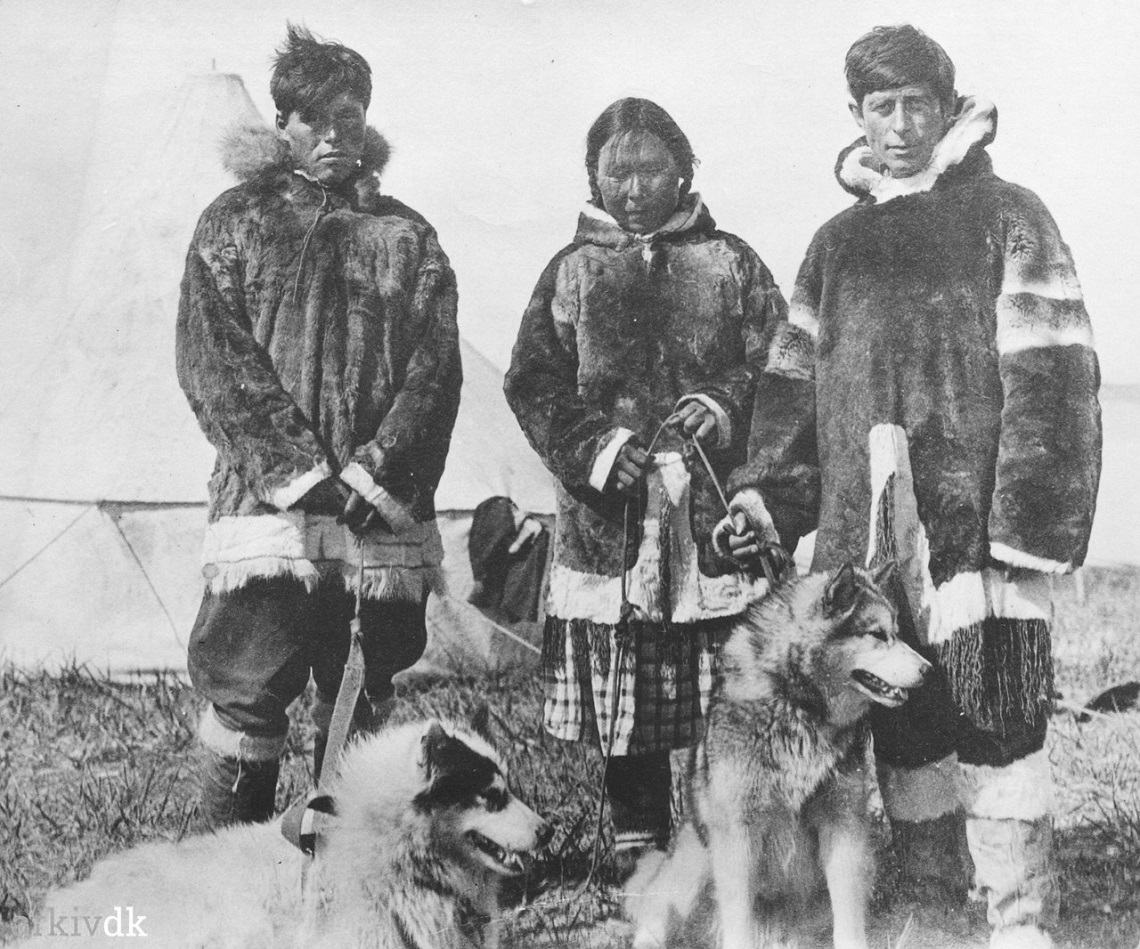

The group consisted of Rasmussen and two young Greenland Inuit who were adventurous and keen to travel into these unknown lands. Miteg was a gifted dog handler and his female cousin, Arnarulunguaq, was a skilled seamstress, cook, and master snow-hut builder. They had two long sleds full of gear along with 12 dogs. They knew they would be on their own and unable to communicate with the outside world for at least a year.

In March 1923, the party headed off in the snow in a north-westerly direction. As before, on meeting different Inuit groups, they would stay with them for a period of time. They lived off marine fare and also hunted caribou and musk ox. On reaching the Northwest Passage, they journeyed due west which took them to the Mackenzie Delta before they entered Alaska. They continued to Point Barrow on the Arctic Ocean coast, before finally ending their journey at Nome on the west coast of Alaska.

The three explorers from Greenland had succeeded in completing the longest dog-sled journey in polar history and the first people to sled the entire length of the Northwest Passage.

Before leaving the region, Rasmussen managed to obtain permission from the Russian authorities to meet some of the Siberian Inuit across the Bering Strait. After chartering a schooner from Nome, he was allowed just a brief period to meet some of the Inuit people living in the region. Rasmussen realised he had travelled to the limit of Inuit culture.

He concluded that the Inuit shared the same language, legends, and similar traditions and had migrated eastwards, out of Asia, across North America to Greenland. After three and a half years of the fifth Thule expedition, travelling over 19,800 miles, visiting thousands of Inuit, it was time to head home.

Rasmussen wrote,‘From the bottom of my heart, I bless the fate that allowed me to be born at a time when Arctic exploration by dog-sled was not yet a thing of the past.’

HIS LATER LIFE

There were shorter sixth and seventh Thule expeditions which both took place in eastern Greenland and involved studying Inuit culture. During the seventh, Rasmussen was also looking for suitable locations for an Inuit film he was helping to make. It was there where he became ill and was transferred to Copenhagen by ship during which time his condition deteriorated.

In hospital, a rare form of botulism was diagnosed and at the same time he developed pneumonia. Rasmussen Rasmussen passed away in December 1933 at the age of 54.

It was the end of an exceptional Inuit-Danish man’s life. Rasmussen’s love of polar environments and the Inuit culture led him to complete journeys right across the Arctic world. His travels in some of the most inhospitable areas of Greenland and across North America by dog-sled were simply extraordinary.

As a lover of Inuit storytelling and culture, it’s befitting that Rasmussen himself became an Arctic legend in his own lifetime…

WHO’S WRITING?

Roger Bunyan has been contributing to Adventure Travel magazine for many years. Always fascinating, insightful, and entertaining, it was only natural that the stories of these adventurers were compiled into a book. Against All Odds: The Stories of 25 Remarkable Adventurers is Roger’s first Book, and in it he takes a more in-depth look at the adventurers he writes about in each issue of this mag. The amount of time, effort, and research that he has put in is astounding, and it makes for captivating reading. To get your copy, head on over to www.hayloft.eu.

Roger Bunyan has been contributing to Adventure Travel magazine for many years. Always fascinating, insightful, and entertaining, it was only natural that the stories of these adventurers were compiled into a book. Against All Odds: The Stories of 25 Remarkable Adventurers is Roger’s first Book, and in it he takes a more in-depth look at the adventurers he writes about in each issue of this mag. The amount of time, effort, and research that he has put in is astounding, and it makes for captivating reading. To get your copy, head on over to www.hayloft.eu.