We spoke to former SAS man Phil Campion to find out how to spot and survive an avalanche as well as the vital equipment you should have on hand. Here are his top tips…

Avalanches are dependent on several factors: the weather, location and terrain, including the condition of surrounding slopes and sun exposures, the depth and layers of snow, and human behaviour. Most avalanches occur within 24 hours of a heavy snowfall: the more snow that falls, the greater the pressure on the weak points. Around 90% of avalanche fatalities, however, are triggered by human activities.

As skiers, snowboarders and those on snowmobiles move down a slope, the extra pressure exerted on the snow pack creates fractures resulting in a dry snow slab avalanche. While predicting an avalanche is difficult, surviving one is possible. Here’s what you need to know.

Basic preparation

The safest approach to any avalanche is to avoid it at all costs. Before you even think about venturing out on a slope, do your homework: consult the local avalanche advice centre for a current weather forecast, find out what the avalanche danger rating is and check the snow pack conditions.

Despite the common misconception, noise does not trigger an avalanche. However, too many people on the slope at once can do. If you’re travelling with a group, try to spread out; it also means that, if an avalanche does occur, the survivors can help the victims, or at least advise rescuers of their location.

Be aware of everything happening around you. Look for recent avalanche activity: any fracturing, sloughing or wet slides on the slopes or ridges. Listen for hollow noises and whoomphing sounds when moving across the surface: the snow pack may be fracturing. If the snow doesn’t appear to support you, it’s not safe.

Choose gentler slopes for skiing: the steeper the slope, the greater the likelihood of an avalanche. Slopes that have an angle of between 30 and 40 degrees provide perfect conditions for the snow to slide. If you have to travel down a section that you’re unsure of, seek an alternative route, or travel one at a time to keep tabs on each other. Try to avoid the side of a mountain that faces the prevailing wind as this can cause large amounts of snow to gather in one place, increasing the likelihood of a slab avalanche.

Surviving an avalanche

In a rapid snow slide, you’re likely to get swept up in its path and will most likely crash into anything that lies along the way, including rocks and trees. At impact, snow will fill every available orifice, including your mouth, ears, nose and eyes. You’ll lose your bearings quickly and may not know which way is up, becoming entombed in an impacted mass of snow that will make it impossible to move or, worse still, breathe. Chances are that your clothes will be ripped from you, too. If you want to survive this experience, try and remember some basic rules.

If the snow knocks you down, get rid of as much equipment as you can or it will pull you down into its depths. If you’re skiing off-piste, never use the wrist straps on your ski poles, so that they can be discarded quickly in an emergency. Your best chance of survival is to remain on the surface of the moving snow.

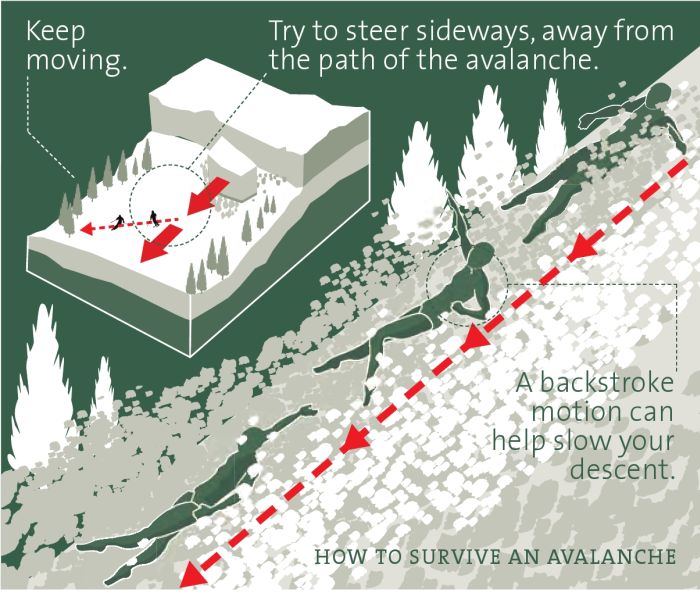

If you’re on your back, attempt to backstroke your way up the hill with your feet pointing downward and your heels digging into the slab of snow to try to slow your descent (see illustration).

If you can, grab on to a tree, but remember avalanches can travel at between 60 and 80 miles per hour, so this sounds easier than it is.

If you find yourself being rolled by the snow, try and hold your breath and curl up into the foetal position. Use your hands to protect your face. As the slide stops, the snow will begin to harden around you like cement. You have only an instant to try to make some air space around your nose and mouth. Fold your arms in front of your face to give yourself as much room as possible and use your body to move from side to side to make more space.

If you’re near the surface, push one arm or leg up to try and break through the surface of snow so that rescuers can spot you. Take a big breath to expand your chest and give you extra breathing room. One of the key causes of death in an avalanche is suffocation, claiming around 90% of victims.

Essential equipment

To avert an avalanche disaster is to go prepared and that means taking the right equipment for the job and knowing how it works.

Transceiver or beacon: If you get buried by an avalanche, this piece of technology will help rescuers find you. Combining a radio that transmits and receives electromagnetic signals, it is highly effective at locating you. Always ensure that you set it to ‘transmit’ when you start out and not ‘receive,’ as the latter will mean you’ll be out in the cold a lot longer than you expected.

Shovel: It sounds basic, but it can move snow five times as fast as your hands, and in an emergency that’s vital. If you’re backcountry skiing, always carry an aluminium shovel in your backpack for a light but effective lifesaver. Metal is far more effective than plastic for removing avalanche debris.

Ski pole/probes: Once the beacon has located a trapped skier, they could be buried so deep that they’re not visible from the surface. A probe can lessen the time it takes to pinpoint their body before expending energy digging, and it’s the only way to penetrate the dense debris from the avalanche. Most collapsible probes are light and compact and far longer than ski-pole probes. Otherwise, you could use a long tree branch as an alternative.

The slab avalanche

Dry: The dry slab avalanche accounts for more deaths than any other type of avalanche. Often triggered by skiers or those on snowmobiles, these occur when a large top layer of hard snow forms over weak, soft snow beneath. As a skier travels over the layer, a fracture occurs within the weak layer, releasing the upper slab. Within five seconds it can reach speeds of 60 to 80mph, and as it builds up pace it will break up into ice-hard chunks that can injure or entomb victims.

Wet: The wet slab avalanche is triggered by thawing snow and can cause a whole slope to slide. It travels much more slowly, at around 10 or 20 miles per hour, and has an appearance a bit like concrete pouring down a slope. Although less likely to cause a fatality, if you’re caught in its path it can still give you a serious injury.

The dry powder avalanche: Usually occurring after a fresh snowfall, it starts to move as a soft slab but gathers speed and width as it travels down a slope. As the snow is lifted on the air, a powder cloud forms, but beneath it is a speeding mass of snow: a mix of air and ice particles. Travelling at speeds in excess of 100mph, this powder avalanche can create a risk of suffocation if inhaled. Although less dangerous than the dry slab avalanche, if caught in one you can easily be pushed over cliffs or end up buried in concrete-like snow.

The beginning of an avalanche

At this stage you still have the chance to escape. If a slab of snow begins moving underneath where you’re standing, you need to act immediately. Try moving to one side or running uphill so that you are above the fracture and on stable ground. If you’re already skiing and you trigger a slab, the only thing you can do is keep moving. Use your skis or snowmobile to build up speed and distance from the avalanche and then attempt to steer sideways to get out of the pathway of the fast-moving snow. The snow moves fastest at the centre of the flow, which is where most of the snow will accumulate, so the further away from this you can be, the better.

The avalanche facts

● You have a 90% chance of survival if you’re rescued within the first 15 minutes of becoming trapped, but that drops to 45% within 30 minutes.

● If you’re buried under the snow, you have around 25 minutes to be rescued before your air supply runs out. Conserve your energy and only yell for help when you hear rescuers are nearby.

● If you’re trapped under more than seven feet of snow, your chances of survival are slim.

This article is an extract from Phil’s book Big Phil Campion’s Real World SAS Survival Guide. It costs £14.99 and is available from www.quercusbooks.co.uk.

Intro photo: Maureen Barlin