OVER THE HILL?

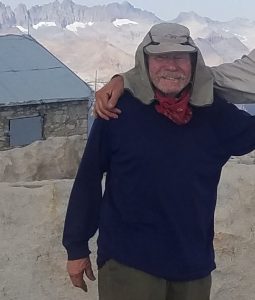

No way! GEORGE GREYBILL may have just turned 80, but that’s all the more reason to trek the JOHN MUIR TRAIL, which stretches for 211 miles through the stunning Sierra Nevada range, California

Standing on the top of Mount Whitney, surrounded by people one-third my age, I thought, ‘You know, that really wasn’t all that hard.’ Whitney marks the south end of the John Muir Trail (JMT) and I was standing on its summit because I’d just trekked all 211 miles of it, including all 10 high mountain passes. The JMT is arguably the most dramatic long-distance trail in North America.

Standing on the top of Mount Whitney, surrounded by people one-third my age, I thought, ‘You know, that really wasn’t all that hard.’ Whitney marks the south end of the John Muir Trail (JMT) and I was standing on its summit because I’d just trekked all 211 miles of it, including all 10 high mountain passes. The JMT is arguably the most dramatic long-distance trail in North America.

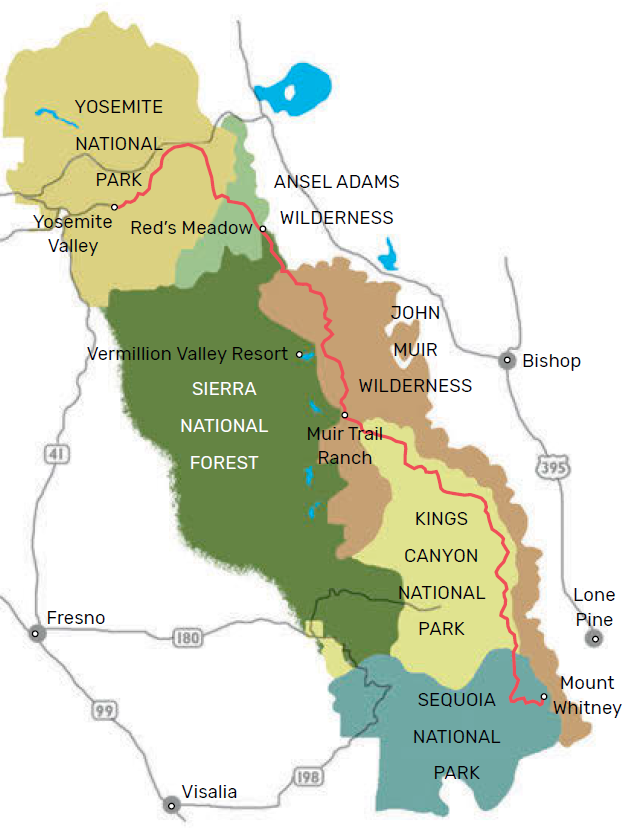

It runs through the Sierra Nevada range, California, from Yosemite National Park to the point where I now stood, 4,421m up Mount Whitney, the highest peak in the contiguous United States. I’d hiked the trail twice before, and those trips had been so memorable I decided to do it one more time.

The fact that I was now 80 years old didn’t seem relevant.

THE PLAN

When I told my son, Dan, that I was doing the JMT again, he said, “I’m going with you!” “What if your boss won’t give you a month off?” “I’ll quit.” When Dan was six, my wife Lyn and I started taking him backpacking. Our trips lasted a full month. We didn’t cover much ground; we just found a good off-trail lake and lived there. By the time he was 16, we had him so indoctrinated he couldn’t face a desk job. He now works as a forester in northern California and has two young children who will start backpacking this summer. Since then, Dan and I have only been able to work in weekend trips, so I wasn’t sure how the dynamic between us would pan out on a three-week trip.

Six months after deciding to do the JMT, Dan and I were in Yosemite Valley looking at a sign with a long list of distances to various destinations. We both felt so well prepared and eager that we weren’t the slightest bit intimidated by the bottom line; it read, Mount Whitney—211 miles.

A late start that first day meant we only hiked 4 miles to bear-infested Little Yosemite Valley. On the way, we climbed past two famous waterfalls, Vernal and Nevada. They were both raging. The bears in our campsite wanted to beg or steal food from us, but they were unsuccessful.

The next two days took us past the soaring granite monoliths of Matthes Crest and Cathedral Peak, through Tuolumne Meadows, and up Lyell Canyon. The passing scenery was very familiar and brought on waves of nostalgia because our long family trips had almost all been in Yosemite National Park. We always came here because there is a pack train network that we could use to resupply. Familiar or not, Yosemite high country is always magical.

OLD AND KNEW

At this point, I noticed some definite changes in my abilities. My endurance level had dropped. I could once carry a pack 15-20 miles a day; now I was pretty much beat by 12 miles, and I was less sure-footed, even though I was using a trekking pole. I began the mental process of admitting I had slipped a little.

Then I reminded myself that 12 miles a day is still slightly above average for any age and that this is not a competitive sport. On the bright side, my lungs were working nicely at 3,000m. The Tuolumne River meanders for 6 miles through the meadows that blanket Lyell Canyon. At the end of the canyon, you begin the climb to Donohue Pass, as the river rushes down past you. At the top of the 3,350m pass, you leave Yosemite National Park and enter Ansel Adams Wilderness. This is only the second of the 10 passes that make up the JMT.

The path over the pass was uneven and rocky, and I fell a few more times. Dan started to voice concerns. He said he thought I needed two walking poles. This gave me some feelings to process. I’d never needed any poles before. I thought they just got in the way and that people using two looked silly. But it did seem that almost everyone on the JMT these days had two poles. Maybe I should try it? It used to be me worrying about Dan’s health and safety on these kinds of trips together; now he was worrying about mine. Well, it is what it is.

Island Pass was our next challenge, which involved crossing a plateau that looks as if it were designed by a master Japanese gardener. The rocks, pools, and flora are all impeccably arranged. From Island Pass the trek descends to Thousand Island Lake and Garnet Lake, which are both dotted with small, inviting islets. The imposing hulks of Mount Banner and Mount Ritter tower over the far ends of the lakes.

On day five we arrived at Devil’s Postpile National Monument and the nearby resort of Red’s Meadow. As well as being a good resupply point, it also has a store and restaurant. It’s also the last place you can park your car and be just steps away from the JMT. From here on out, you’re entering into the John Muir Wilderness.

SUPPLIES AND DEMAND

Two days later, we passed Purple Lake and pitched camped at Lake Virginia. We swam in the icy water and beat our dirty laundry on the rocks before pressing on over Silver Pass the following day and dropping down to Mono Creek. Here, we left the trail for a few miles and camped near Lake Thomas A. Edison. The aim was to catch the morning ferry across the lake to Vermillion Valley Resort (VVR), where we’d retrieve our resupply boxes. VVR is very hospitable to trekkers and your first drink is on the house. You can also get a shower and rummage through boxes of food, supplies, and gear that other hikers have abandoned; the meal servings are huge.

VVR is where I first fell prey to the trekking bug. Some years ago, I was eating breakfast here with Lyn when a group of unusual-looking people sat down at an adjacent table. They were wiry and weather-beaten and gave off a raised-by-wolves vibe. They proceeded to eat enormous platters of food, which they washed down with beer. They turned out to be trekkers from the JMT. After they told us a little about their trip, I said to Lyn, “I want to do that — or, at least, I want to look like that!” It was during my rummage through the abandoned gear box in Vermillion Valley that I found a pair of high-end trekking poles, one of which was broken. I took the good one and decided I’d have a go at two-pole trekking.

Two days later, we descended from the sixth pass and navigated a difficult crossing of the South Fork of the San Joaquin River. We’d veered off the trail a bit to soak in the Blayney Meadows hot springs, which I highly recommend. We were now almost exactly halfway to Mount Whitney.

The next day we entered King’s Canyon National Park. We followed the San Joaquin upstream as it plunged down a rocky gorge until it was met by the large tributary of Evolution Creek. The JMT follows this creek upstream as it races down from Evolution Valley. In the valley, the stream meanders through broad, grassy meadows for several miles. We spent the night near the foot of the mountain named ‘The Hermit’ and watched it light up as the sunset.

Waking early, we made the hard climb up to Evolution Lakes and another hard one over Muir Pass. Muir Hut, perched in the pass, honours the naturalist for whom the John Muir Trail was named. Lakes on either side of the pass are named for Muir’s daughters, Wanda and Helen. The hut is a marvel of minimalist architecture. I’ve always wanted to spend a night there, but I’ve never arrived at the end of the day. The pass is popular with marmots, the alpine version of groundhogs.

We dropped about 450m from the pass and set up camp that night in a light rain. In the morning we completed the descent and continued on to Big Pete’s Meadow and Little Pete’s Meadow. In a weird twist of nomenclature, Little Pete’s Meadow is actually much bigger that Big Pete’s Meadow. I’ve no idea why. Perhaps there were two Petes.

PASS IT ON

We wanted to try to make it over Mather Pass the following day. We were still 900m below it, and the storm clouds were moving in again. This wasn’t typical Sierra weather. Usually, the clouds build up every day for a week or so, there is one late afternoon shower, then the next day is clear, and the cycle repeats. But it seemed a weather system had gotten stuck over us. Now we had rain or a threat of rain every day in the late afternoon. True to form, we gained another 200m and set up camp as the heavens opened. The next day we made the steep climb to Palisade Lakes at 3,200m and another long climb to Mather Pass at 3,650m.

The high passes were coming one after the other now. They were all hard climbs, but the effort never got tedious thanks to that special flavour of elation you feel when you arrive at the pass, like summiting a difficult peak. If other people are in the pass, they are always all happy, and there’s a sense of being simultaneously in the past and in the future. If you look in one direction, you can see where you’ve been, and in the other, you have a clear view of where you’re going.

On the other side of the pass, we descended to a rocky, treeless plateau. As we travelled south, the terrain gradually transitioned from lush, forested tranquility to dry, stark grandeur. We set up camp when we reached the tree line. Dan went off to explore the surroundings and it was then that I did something careless. While walking over rocky ground, I tripped and fell, hitting my side hard on a boulder. It felt like I’d broken a rib, and the pain was sensational. My first thought was, ‘I’ve ruined the trip!’ I wasn’t worried about getting out. I knew all I had I had to do was push the red button on my PLB1 Beacon gadget and somewhere a helicopter would take off. The real tragedy was that Dan had been dreaming about this trip for years, and now I’d screwed it up for him.

When Dan got back to camp, I couldn’t bring myself to tell him what I’d done. I decided to take some painkillers, get a good night’s rest, and reassess the situation in the morning. When I woke up, I took another tablet and the pain subsided again. Shouldering my pack as we left camp, I realised my ribs felt better with the pack on somehow, and I was determined to finish the trail.

Pass number eight is Pinchot Pass, where we camped by a stream on the other side. I’d been looking forward to reaching Rae Lakes, where we camped the next night. This area is a popular destination even though it’s a long hike from all trailheads. A mountain with the shape of a fish’s dorsal fin towers over the lakes. Unsurprisingly, it’s known as ‘The Fin’.

SUMMITING WHITNEY

Glen Pass is just above Rae Lakes and is the penultimate pass on the trail. That day, we were caught in a hailstorm and were pummeled with hailstones large enough to hurt. We camped at the base of the final pass, Forester Pass, which at 4,023m is the highest on the trail. These passes at the south end of the JMT are similar in that the north side is a long, winding ascent, and the south side is a nearly vertical cliff, into which the trail has somehow been carved.

As we hiked, we continued to marvel at the amount of work it took to build the JMT. The entire trail is amazingly well-engineered and maintained. There are only a few places where hand-over-hand scrambling is required and it’s relatively safe, though you do need a head for heights. By the time we reached Forester Pass, I’d weaned myself off the hard drugs and switched to ibuprofen. My optimism had been restored.

On day 20 of our trek, we said goodbye to the last trees at Timberline Lake. We were now at the foot of Mount Whitney. We climbed to a small tarn somewhere above 3,650m and set up base camp for our ascent of Whitney the following morning. This spot has the highest water near the trail.

We started up before daybreak. Headlights could already be seen moving up the trail far above us. There were a few scary spots and a few sections that required scrambling, but overall, the climb was fairly easy. When we topped the summit in the late morning, it was like arriving at a party. There were 20 or 30 people there already and they were all elated — everyone taking everyone else’s picture and writing in the summit log.

We had completed the trail in 20.5 days, including one rest day, which is a little faster than average. The summit is the official end of the trail, but not the end of the hiking. The nearest highway is 11 miles away and 1,800m below. We were both radiantly happy on the way down. In fact, my elevated state lasted for weeks, and my spirits were buoyed by frequent flashback memories of the JMT. In phone conversations with Dan, he confirmed he was experiencing the same thing.

Back at my computer, I started looking up statistics and records for the John Muir Trail and discovered that I was the oldest person to hike it — by five years! I felt more puzzled than proud.

And so, the moral of the story is this: being old is not in and of itself a physical handicap. If your health is generally good, dig out your old backpack and put it on.

WHO’S WRITING?

We emailed George for an ‘about the author’ bio and got his out-of-office instead. It reads: ‘I will be backpacking and will not have cell or internet contact. If anyone asks about me, tell them I’ve gone to a better place.‘ Which says it all really

We emailed George for an ‘about the author’ bio and got his out-of-office instead. It reads: ‘I will be backpacking and will not have cell or internet contact. If anyone asks about me, tell them I’ve gone to a better place.‘ Which says it all really