A LIFETIME OF ADVENTURE

One of Britain’s most REVERED mountaineers, SIR CHRIS BONINGTON, has spent his life EXPLORING the highest heights and far reaches of the Earth, ACHIEVING climbing feats that no one thought possible, and he owes it all, he says, to his basic sense of ADVENTURE…

Thanks to the wonder of Zoom, I’m in Sir Chris Bonington’s living room. His unmistakable Father-Christmas face breaks into a huge, delighted grin as mine appears on the screen and as he waves excitedly back, I really do feel as though I’m being welcomed into his home. The shelves are stacked with volumes of books on history, a lifelong passion of his, and on the wall behind his head hangs a magnificent rendering of the Old Man Of Hoy, an iconic sea stack off the coast of the Orkney Islands in Scotland, done in oils by an artist friend.

He gestures to the wall behind my head where there’s a not-so-magnificent rendering of a car, done in finger paints, by my daughter when she was a baby. He wants to know all about it, and about the artist. He’s interested in me, genuinely curious and pleased to make a new acquaintance. And that’s the magic of being in conversation with Sir Chris. That at the age of 86, and with so many incredible life experiences under his belt, his almost childlike enthusiasm for learning more and experiencing something new means that he lives his life in a state of constant adventure. From my dingy dining room table, I’m thrilled to be sharing the next hour of it with him.

EARLY DAYS

Sir Christian John Storey Bonington was born in Hampstead, London, in 1934, something he’s eternally grateful for as it gave him, he says, the chance to experience the best years of mountaineering. “I was incredibly lucky to be born when I was, to have come into young adulthood immediately after the Second World War,” he confesses. “There were so many huge opportunities that we had, so much hadn’t been done. None of the 8,000-metre peaks had been climbed. And then, of course, Annapurna had its first successful French expedition [in 1950], and then Everest was climbed [in 1953]… but they were all in the very, very early stages of that. My generation had so much we could actually do.”

If there’s one thing that defines Bonington, it’s that he’s a doer. Even growing up in the city, the great outdoors beckoned to him from an early age, encouraging him to seek out those wilder places amid the concrete jungle and explore them to the fullest. “I always climbed,” he says, proudly. “As a kid, getting out on the Hampstead Heath where I was brought up, I climbed every tree I could possibly find. I suppose it’s that basic sense of adventure.”

His innate love of discovery led him first to Dublin, where Bonington climbed his ‘first little hill’ just beyond his grandfather’s house, and then to Wales, where aged 15, he took on his first real climb. “I persuaded a mate of mine from school, Anton, to go with me and we hitchhiked up to Snowdonia, to climb Snowdon. We chose one of the hardest winters in years!” he scoffs with a twinkle.

“Once we got ourselves to Pen-y-Pass we very nearly turned back. But there were a couple of guys in the car park who had ice axes and we thought, ‘Well, if we follow them, we’ll be alright’. We got about halfway along the pig track that traverses below Crib Goch and then we were avalanched. I suppose that could have been the end of Bonington had we been swept off the cliff!” he laughs. “We were lucky, though. We had a clean run and only got swept down about 3-or-400 feet. We got up, shook ourselves, and walked back.”

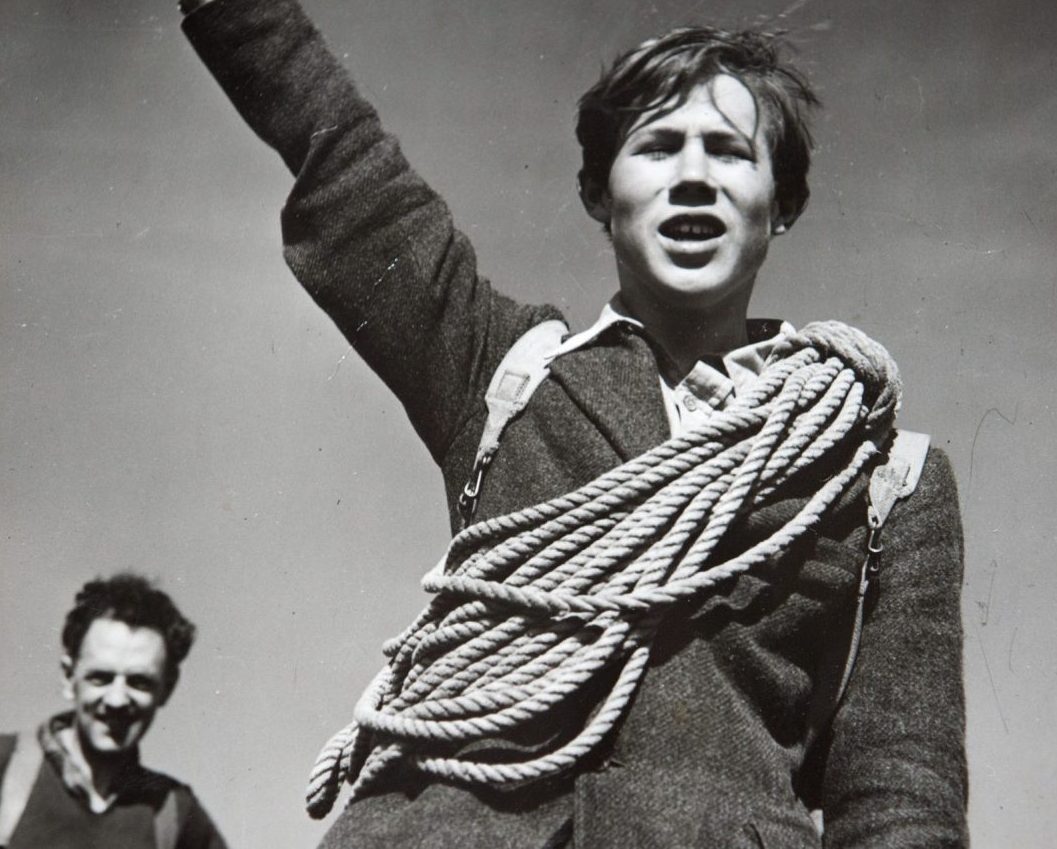

While the experience was enough to put Anton off climbing for life (he caught a train home the very next day) it had the exact opposite effect on Bonington. “I thought ‘this is brilliant!’,” he whoops, both fists in the air. “That experience really captures it. Essentially, I’m excited by risk, and I was just totally hooked.”

A chance encounter that same trip with two climbers in a Welsh B&B inspired Bonington further with their stories of mountaineering daring-do — “I didn’t even know that climbing existed at that stage. It sounded incredible”— and misadventures in Wales soon gave way to more successful climbs in Scotland, thanks to a young Scottish climber named Hamish MacInnes.

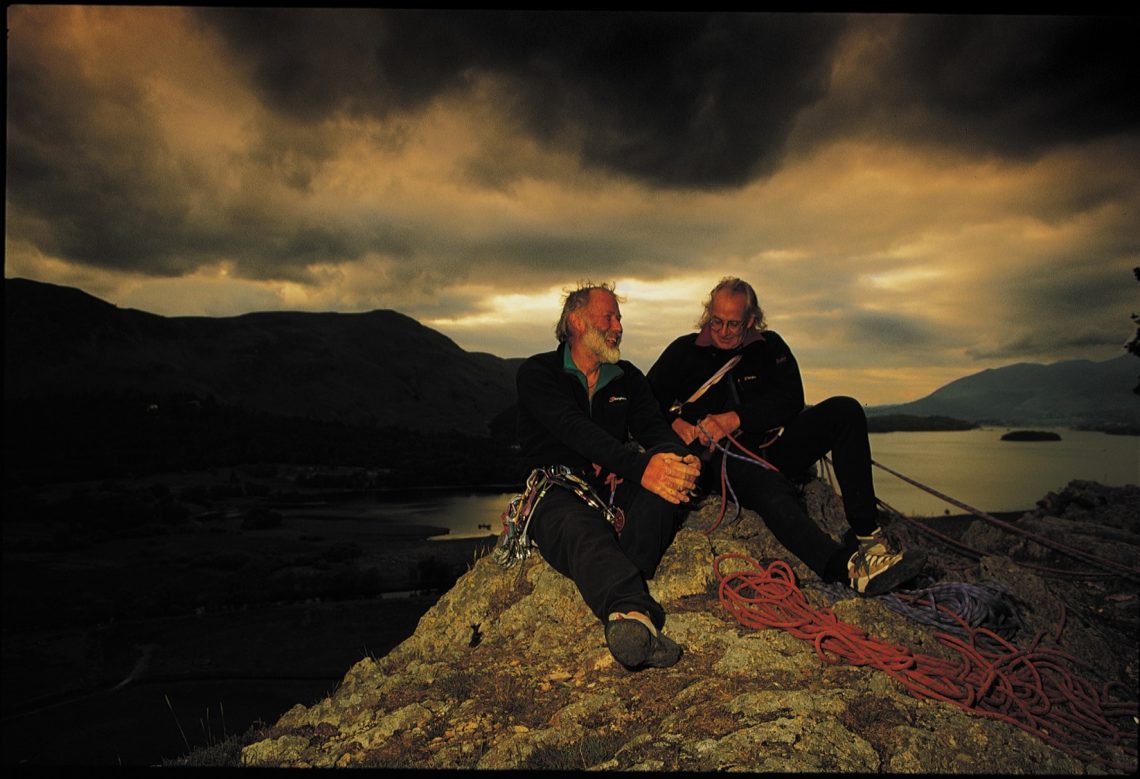

“What excited me was what I could actually reach,” he enthuses. “Once I discovered climbing, I discovered I could hitchhike up to Scotland. I was lucky I stumbled across Hamish on my first ever trip there when I was young. He was five years older than me and a very, very good mountaineer, and because the guys he was climbing with had gone and there was no one else, he resigned himself to taking me, this complete novice, climbing. We did a series of very hard climbs and established a friendship that’s lasted throughout our lives.”

Once Europe became an option, however, Bonington soon found a new playground: the Alps. “When I started climbing, I couldn’t get to the Alps. My mum and I had never been abroad, what with the war and everything else. Once I went into the army, of course, I was eventually stationed in Germany, so suddenly, then, the Alps were within my reach. The very first holiday, I wrote to Hamish and said, ‘How about climbing in the Alps?’ I got a reply back immediately: ‘Absolutely. Yes. Delighted. Meet me in Grindlewald’. We’ll go for the north wall of the Eiger.”

Ambitious? Maybe. But the lads’ optimism to take on the biggest, deadliest rock face in the Alps wasn’t unfounded. “I think we’d have had a sporting chance of climbing it,” he admits. “Hamish at that stage was perfectly capable of doing it and, technically, I was always better than him. I was a very, very good natural climber.” The weather was not on their side, however, and the pair were forced to abandon their plans, but the mystical pull of the Alps remained Bonington’s driving force for years to come.

HIGHS AND LOWS

During the early 1960s, Bonington’s climbing career reached new heights in the Himalayas, with historic first ascents on Annapurna II (7,937m) in 1960 and on Nuptse (7,861m) the following year. But it was the pull of the Alps and the Eiger (3,967m) that drew him back to Europe, and on his return journey from the Himalayas, he called in at Grindlewald, making the first British ascent of the north face of the Eiger in 1962. But in a career bejewelled with so many dazzling achievements, which ones stand out now, looking back?

“I suppose the southwest face of Everest, which was a huge organisational leadership challenge,” Bonington muses. “I mean, five very strong expeditions had tried and failed on it. And I saw very clearly that the challenge was not technical climbing it was actually logistics, planning, and organisation. These were things that I was fascinated by and I discovered that I was quite good at leading. The Himalayas became really interesting when I started leading expeditions there. There’s something wonderful about the Himalayas. It was my next dream, if you like.”

Alongside expeditions that stand out for all the right reasons there are inevitably some memories that are much harder to live with. During a lightweight Alpine-style expedition on K2 in 1978, Bonington lost his good friend Nick Estcourt when a snow slab avalanche broke loose as the team was crossing a snow slope. Doug Scott, who was also part of the group, survived by sheer chance as the avalanche swept him into a ditch where he was safely wedged by his huge backpack. Estcourt, who was following behind, wasn’t so lucky.

“Nick was one of the closest friends I’ve ever had,” Bonington recalls with warmth. “We climbed together, lived together in each other’s houses, our children were friends… When something really hard happens to you, particularly the loss of very close friends, coming through that and living with that level of guilt that I still have, where I as leader of that expedition made some mistakes, and that because of that mistake, someone died, those are very difficult things to come to terms with.”

So how do you head back out into the mountains after enduring an experience like that? “Because of one’s own temperament. And my temperament is that you accept what’s happened in the past, you learn from what’s happened, but life goes on,” Bonington affirms. “There’s no point in living in grief in the past. And I think it’s something all of us have got to do. It doesn’t, in any way, reduce the kind of love we had for that person. But that happened, and we’ve got to go on. It’s living in the present and going to the future that enables all of us to get through life well.”

As well as overcoming loss in the mountains, Bonington has also faced some truly gruelling experiences, including his infamous descent of the Ogre (7,285m) alongside the late Doug Scott, whom he describes as ‘one of the greatest all-round mountaineers Britain’s ever had’. “Technically, the hardest climb [I did] was Everest itself. But some of the toughest were smaller expeditions where things went terribly wrong,” he recalls. Previously unclimbed before Bonington and Scott’s successful ascent in 1977, the Ogre is a complex mountain in Pakistan’s Karakorum range. The pair made it to the top without incident but a near-fatal accident as they were heading back down turned the climb into a test of sheer endurance.

“Doug had taken his crampons off to do some very hard climbing lower down. He slipped on the very first abseil and did this huge pendulum fall, smashing into a corner of the rock,” Bonington grimaces. “He brought his legs up to break the fall and in doing so broke both legs. So there we were, just below the summit of this incredibly complicated mountain.

Doug ended up having to crawl all the way down the mountain — we were a very small expedition anyway, we couldn’t have carried him down. By this time, we’d run out of food; we ended up going for about five days without anything to eat. It was just a huge struggle, all the way down. That was undoubtedly the toughest trip I’ve ever had.”

As well as the lack of food and Scott’s injuries, which would have been regarded as a death sentence by most climbers, Bonington suffered three broken ribs in the descent. So, what goes through a person’s mind when they find themselves in that kind of situation?

“Just staying alive!” he laughs. “Broken ribs are incredibly painful unless you can stay absolutely still, but if you laugh or cough — the jab of intense pain! On top of that, I snore a lot.” (my turn to laugh). “The other three were in one little tent and I was in the other tent by myself, ostracised because of the snoring. So I just focussed on staying alive and getting through it. I was always determined to come out alive. Having a strong sense of survival got me through.”

Speaking of tent buddies, who would Bonington choose to share a tent with halfway up Everest? “I think you really want someone who’s a good laugh,” he smiles. “I’d take Nick [Estcourt], actually. He was a dear, dear friend, we got on incredibly well and had the same kind of sense of humour. Sense of humour, I think, is the most important thing in the world. Never, ever go anywhere with anyone who doesn’t have a sense of humour.”

Does he have any regrets about the mountains he didn’t climb? “There’s no point in looking back or wishing things were otherwise or wishing you could do it again, because you’ve done it all,” he says, matter-of-factly. “I’m incredibly lucky in what I’ve done, the experiences I’ve had, both physical exploration of going where people haven’t been before, but also, mental exploration. All of these things add up to a lifelong commitment to adventure.”

THE NEXT GENERATION

The world of mountaineering has changed immeasurably during Bonington’s lifetime, with new firsts being achieved on K2 just this winter, the next generation of greats is emerging, something he’s excited for. “K2 is a very, very difficult, challenging mountain and that Sherpa team, working together, climbed it in superb style,” he says, emphatically. “Admittedly, they were very, very lucky in that day that they went for the summit. But they’d got into that position by superb teamwork and very good planning. It was absolutely fantastic, but it was incredible as well.”

What makes a good natural climber, then, according to Sir Chris? “Firstly, you’ve got to have the physical gymnastic ability to climb. But climbing is dangerous, so you’ve got to be attracted to that kind of element of risk and danger, and be good at handling risk and danger as well. The first time I went on to the north wall of the Eiger, I was worried and afraid, then the moment I started climbing, the fear just vanished. You’re completely immersed in the climb itself. Being able to handle that dangerous element and stay cool and calm, that’s what makes a good climber.”

And now? What is there to fear when you’ve faced fear itself? “I think old age to a degree,” he says thoughtfully. “Losing one’s marbles. I’ve always been a bit forgetful, but I’m really forgetful these days! Physical disability you cope with. But your mind and your capability of thinking clearly, that’s the thing I value most and the thing I’d be most afraid of losing.” As well as new firsts being achieved in the mountains, developments in gear, equipment, and technology have made huge leaps in the last 70 years, taking expeditions and exploration to a whole new level.

“My first pair of boots were a pair of Clinker nailed boots,” Bonington chortles. “The other biggest thing was getting something that is both totally waterproof but also breathes. Back then, there was nothing that did that. If it was raining, you got very, very wet. And then polyurethane came in. It’s completely waterproof, but of course, you sweat like hell inside there. Gore-Tex was one of the most revolutionary things to push climbing forward.”

Despite all the advances in climbing gear, there’s only one piece of kit Bonington wouldn’t be without. “Pre-Kindle, I desperately needed a stock of good paperbacks when I went off on an expedition,” he confesses. “Once Kindles arrived, I definitely needed that and a really good solar-powered charger, to charge it.” His choice of reading material? “I’m deep into history and historical novels. I also enjoy military history; if you’re planning an expedition, military history is all about logistics.”

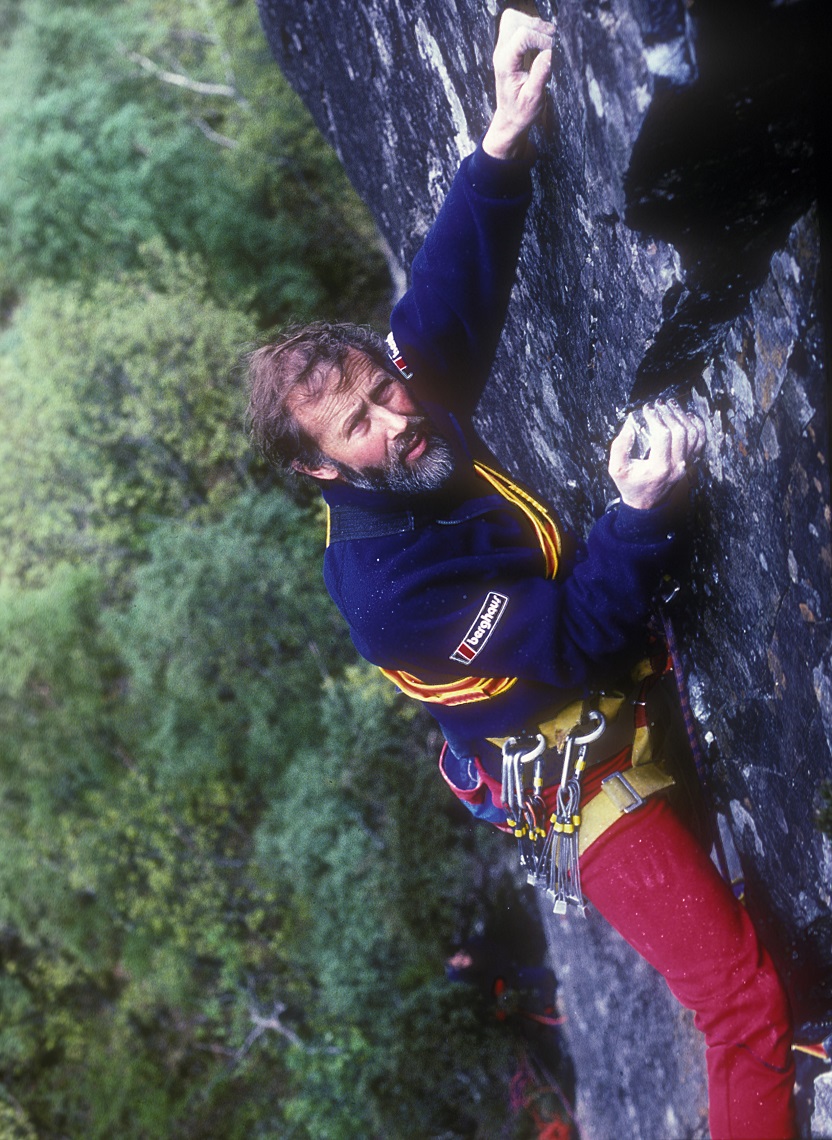

During his longstanding partnership with Berghaus, Bonington has been involved with the company’s gear development alongside fellow athletes like Leo Houlding. “Leo is brilliant at gear,” he exalts. “I’m less practical, but I put in my ideas. I insist that what you need is gear that functions really well but also makes you look and feel good, both for high-end people but also for the person going out into the hills for the first time. And I think [Berghaus] is doing that. Their values are also extremely good, they’ve always had a strong environmental ethos.”

Environmental change is a big factor that’s come to the fore during Bonington’s life outdoors. “I think that’s the most disturbing thing of all,” he says sadly. “You can see we have got serious climate change and I think — I hope — there is still just enough time to slow it down, but to make that happen you’ve got to get every single nation in the world aware of it and making difficult, painful decisions to combat it. Climate change is going to make it almost impossible to live on this planet of ours, we’re destroying it.”

Bonington’s love of the natural world is one that’s still as strong today as it was back in the days on Hampstead Heath, where he still enjoys walking. And although he’s pretty certain he’s hung up his harness for good, there’s no quenching his desire to roam. “I think it would be unrealistic to attempt Hoy again,” he laughs when I probe him about future plans. Bonington famously made the first ascent of the sea stack in 1966 alongside fellow climbers Rusty Baillie and Tom Patey.

The event was televised and over 23 million people watched the trio take on the 137m objective off the coast of Orkney. Bonington made his second ascent 48 years later alongside Leo Houlding in celebration of his 80th birthday, a staggering feat and one he admits filled him with fear, but also reaffirmed his belief in making every single day mean something.

“I want to carry on walking now,” he smiles. “I want to travel again and wander through lovely wild, natural places. The one piece of wisdom I’d like to share is this: live life to the absolute full in every kind of way, and in that sense as well, give back.”

To watch Sir Chris Bonington’s 2014 ascent of the Old Man of Hoy, see www.berghaus.com/ambassadors